RUSSELL — Liz Massa was craving rural life when she moved from Springfield to her dream home in Russell in 2010. It wasn’t long before she had to flee.

One evening a few weeks after moving in, she ran barefoot to the State Police barracks in Russell. Her partner had been punching her, and it was far from the first time. A judge later granted her a restraining order, court records show.

State troopers gave Massa a card for the Hilltown Safety at Home program, created and at the time run by the Southern Hilltown Domestic Violence Task Force.

Massa didn’t know what to do next. So she called the number on the card, and the next day, Gail Bobin, who worked for the task force’s program, was at her door.

If Massa hadn’t gotten the card and called, she said, “I don’t know where I’d be today.”

For 25 years, the task force has been helping people like Massa in the hilltowns by addressing the unique challenges residents face, such as increased isolation and scant transportation options, when confronted with domestic violence.

In 1998, people convened a conference in Huntington and started the task force. In the spread-out hilltowns, it could take police a long time to respond, especially in winter, said Monica Moran, a task force co-coordinator involved since the group’s start.

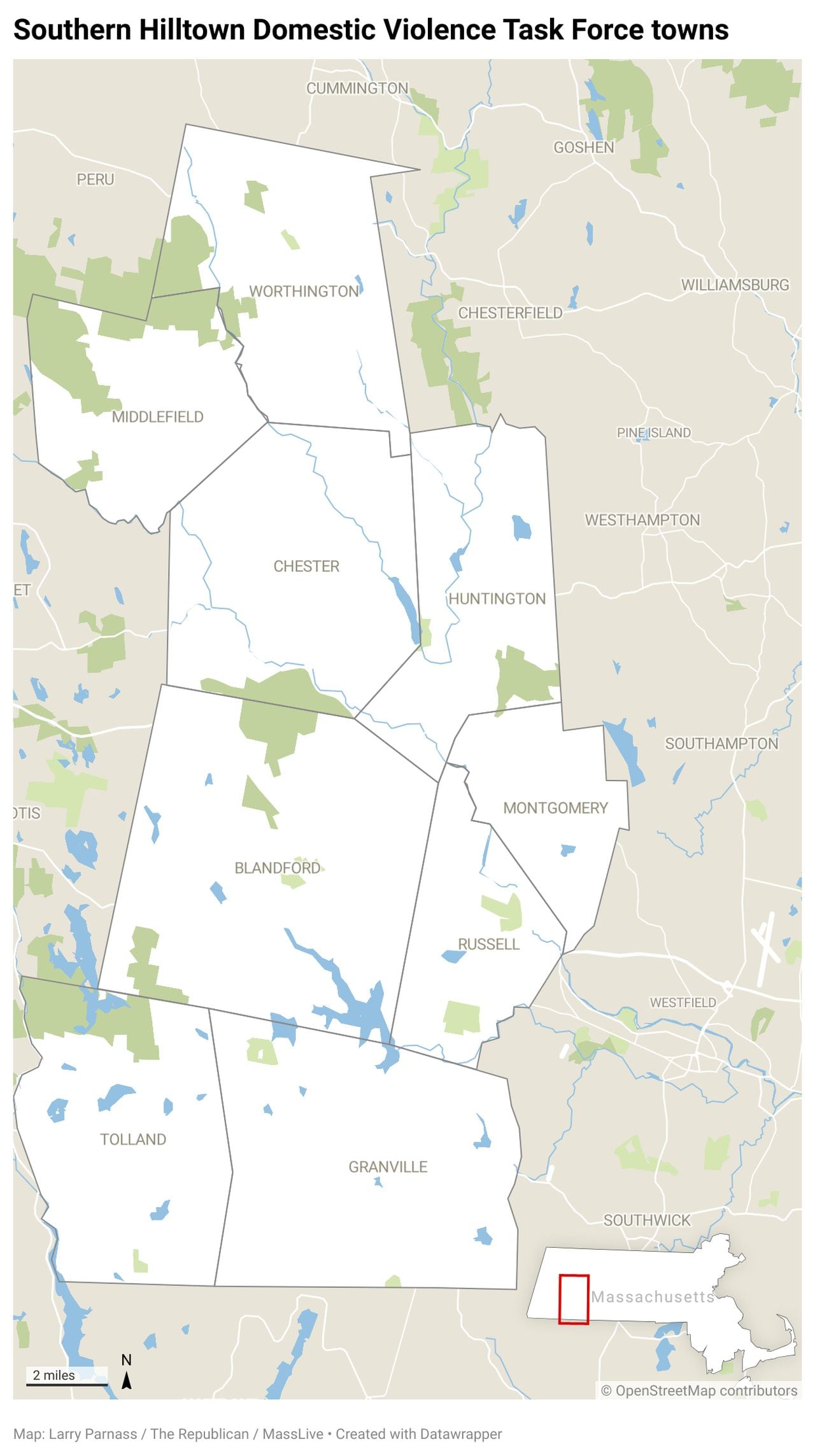

Today, the task force works in nine communities: Russell, Chester, Blandford, Huntington, Worthington, Middlefield, Tolland, Granville and Montgomery.

Since its founding, the group has evolved and grown. It has worked on education programs in schools, advocated for policy changes and helped start a helpline for abusers who want to change.

A few years after its formation, a tragedy in Blandford underscored the need for the group. In May 2002, Karen Trudeau was killed by her estranged husband, who then died by suicide. That came after she tried several times to get help through the legal system, according to the task force.

“A lot of people in the community were mobilized by that event,” Moran said. “The woman who was murdered had really tried to access the court systems. And the court system failed her.”

Trudeau’s husband violated a restraining order five times, according to The Republican’s reporting at the time. The month she was killed, she filed multiple criminal complaints about his violations of the order. When he appeared in Westfield District Court for those and other charges, he didn’t face any changes in his pre-trial release, according to The Republican.

The task force wrote a report analyzing her case and advocated for changes in the legal system. Westfield District Court, for example, tightened procedures to better ensure someone like Trudeau would not “slip through the cracks,” Judge Philip Contant told The Republican in 2005.

Meeting people where they’re at

In the early 2000s in the hilltowns, some of the closest options for survivors to get help were Northampton and Springfield, but their distance made them out of reach for many — the drive from Russell to Springfield, for example, is about 35 minutes.

So in 2006, the task force created Hilltown Safety at Home. The program provided transportation to court and offered to meet with survivors at home, if it was safe, or elsewhere if it was not.

Advocates also looked through police logs and would follow up on domestic violence-related calls and offer help, rather than waiting for someone being abused to call them. “This was a different model,” Moran said. Later, the program grew too large for the task force and in 2015 it was taken over by Hilltown Community Health Center, which continues to run it.

Being in a rural community can magnify the isolation survivors experience, said Donna Larocque, a task force co-coordinator. The physical isolation itself can also pose dangers.

Datawrapper

Before moving to Russell, Massa lived in East Forest Park in Springfield, where homes are close together. In the hilltowns, her home was secluded. “It was a worse situation. If something had happened to me, my house was remote. … He could have terrorized me for weeks and no one would know,” she said.

Repeatedly, Bobin would see situations where someone would abuse their partner and then leave with the household’s only vehicle, stranding the partner in the hilltowns.

“Where are you going to go?” she said. “Even if you get the local police to come and do a restraining order with you, do you think the abuser is going to come back the next morning and let you take the vehicle to court? I don’t think so. … The recognition was that people needed to be reached where they were.”

Bobin remembers getting a call to drive a woman in the hilltowns in a snowstorm 45 minutes to court in Northampton one morning. The woman needed to be in court to get a restraining order against her husband who had left their home with the car. The woman filled out paperwork for a protective order, but then failed to show up in court several times because she had been stranded at home. Bobin remembered the judge asking why she showed up that day, after her previous absences.

“Because she came and got me,” Bobin remembers the woman said.

Program became a lifeline

Bobin worked on the Hilltown Safety at Home program for more than 10 years before retiring in 2018. She worked with hundreds of survivors in her tenure. Melissa Reid was one of those women.

Several years ago, Reid reached out to the task force on Christmas Day. Her partner had smashed her face into the couch and suffocated her.

Bobin was at her house the next day. She looked Reid in the eyes and told her it wasn’t her fault.

“I think it was the first time I was ever told it wasn’t my fault,” she said, choking up. “For me, that was my pivotal moment.”

She remembers taking a minute to think about it. “I was like holy s—. … I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Bobin said she’d see these realizations light up someone’s eyes when she told them she believed them and gave them options about how to move forward. Survivors were used to hearing people say comments like, “He’s not that bad of a guy, he wouldn’t do that to you,” Bobin said.

That was true for Reid. When her partner kicked and punched her or took money from her wallet, she believed it was her fault. “When you’re a victim from an abuser, the only voice you hear is the abuser’s voice,” she said.

The task force and the program was a “lifeline,” Reid said. “I don’t know if I would have ever gotten out if I not had their support,” she said.

Why don’t you just leave, people would say to her. “I wanted to. I really wanted to,” she said. “It’s not that easy. Especially if kids are involved.” The task force and staff from Hilltown Safety at Home treated her with respect. “There’s no judgment,” she said.

The task force and Hilltown Safety at Home though were not the only places Reid tried to get help from. With two black eyes and marks all over her body, she turned to the leader of her church. She was told to pray and that divorce was a sin, she said.

That experience impacted her later when as a volunteer for the task force, she wanted to help educate religious leaders about domestic violence.

“They weren’t trained in it,” she said. The group started an interfaith initiative in 2017 and held trainings for faith leaders.

When the pandemic hit, that initiative paused. It also prompted the group to think about how to help survivors when it was increasingly difficult to leave an abusive relationship when people couldn’t leave home.

“The only thing we can do right now is to ask people being abusive to stop being abusive,” Moran said. The group helped launch a service for abusers who want to change, now a statewide resource called A Call For Change Helpline.

At the task force’s event in October marking its 25th anniversary, Reid read a poem she wrote about her experience. She wanted to speak out. “I find it very frustrating victims are constantly silenced,” she said. “I really want to be able to get these stories out there.”

Reid wants fellow survivors to know this: “They are seen and they are heard. There is help out there. … I’ve done it. I’m 48 years old and I’ve done it.”

The feeling of peace

Hilltown Hikers founder and president Liz Massa. (Don Treeger / The Republican) The Republican

It was through Hilltown Safety at Home that Massa found help.

When Bobin arrived at her home in 2010, she told her how she could move forward and described her options. She told Massa it wasn’t her fault — like Reid, it was the first time she had heard that.

It may seem obvious, but in an abusive relationship, Massa said, “you have to understand you’re in a different type of mindset.”

Bobin also helped Massa be safer by installing deadlock bolts on her doors and making a safety plan. When she had court dates for her divorce and criminal charges filed against her alleged abuser, Bobin would go with her. “Every time, Gail was there,” she said.

She needed the support. “It’s scary,” Massa said. “You have to go and you have to face him.”

Massa, 52, lives a life in Chester unimaginable to her while in a violent relationship. She’s on the town’s Board of Health and Planning Board, and is president of Western Mass Hilltown Hikers.

While still facing abuse, a friend introduced her to hiking and would take her out on Sundays to places like Mount Tom. In the woods, there was no yelling, just peace and quiet. She felt free. “That’s where I started to get that feeling,” she said.

Now she feels that freedom all the time. “Every day I wake up and it’s wonderful,” Massa said. “The whole reason why is because of the task force and Gail.”

If you need support in the hilltowns, you can get in touch with Hilltown Safety at Home at 413-667-2203. Call for Change Helpline can be reached at 877-898-3411. The National Domestic Violence Hotline can be reached at 1-800-799-7233.