This is my tribute to the little helicopter named Ingenuity, which recently suffered a mishap, ending its flying days after three incredible years on Mars.

Ingenuity arrived at The Red Planet on Feb. 18, 2021. It was neatly tucked away on the underbelly of Perseverance, the unmanned car-sized Mars rover, as part of NASA’s Mars 2020 mission.

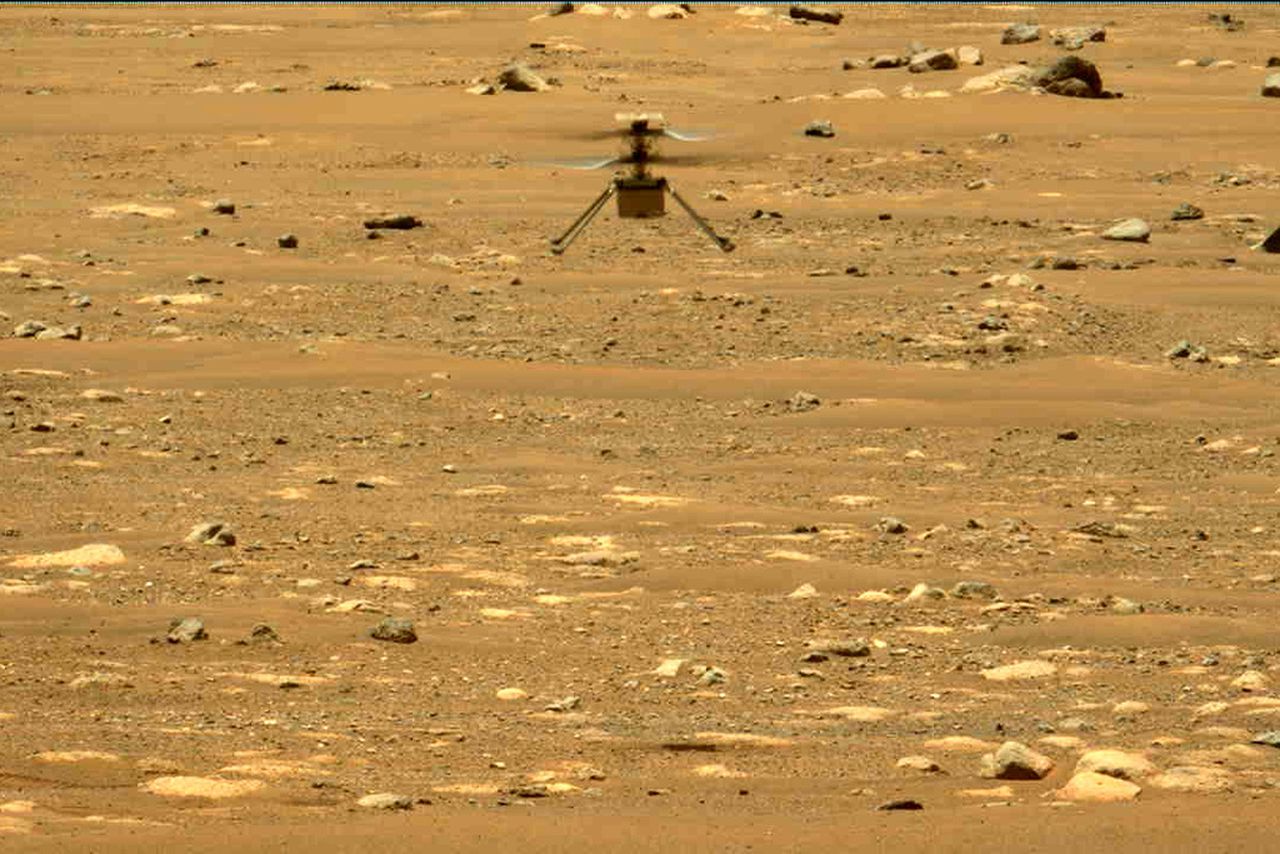

In a series of steps from March 26 to April 3, 2021, Ingenuity was carefully deployed to the surface. In the final stage, Perseverance drove about 13 feet to expose the helicopter to the sky. On April 19, 2021, two months after arriving, it spun up its blades and lifted off briefly, and became the first powered aircraft to fly on another planet.

Extensive testing here on Earth included use of a vacuum chamber to simulate the thin martian atmosphere and a tether to mimic Mars gravity, which is about one-third Earth gravity. Engineers were confident that such flights were possible, but seeing this little machine power its way off the ground provided the proof.

Designers’ plans called for five flights to demonstrate the technology’s feasibility, but in the coming months, enthusiasts like myself watched in astonishment as Ingenuity proved itself in flight after flight. With each charge from its small solar panel, it could fly only 90 seconds, but still managed sweeping aerial vistas of the landscape around Perseverance, and more intimate views, such as the parent spacecraft’s back shell that was last seen as it was discarded during atmospheric entry.

These and the high- quality motion pictures from Perseverance showing Ingenuity itself ascending against those alien hills and flying out of frame, looked so advanced compared to grainy black and white images I so vividly remember from the Mariner 4 flyby in 1965, that I find it hard to reconcile both being from the same lifetime.

Take it from someone whose life began closer to the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight at Kitty Hawk than Ingenuity’s did to Mariner 4′s flyby: This feels like the future.

Ingenuity’s performance in the harsh Martian environment exceeded all expectations, so it was a bittersweet ending when the tips of its rotor blades apparently clipped the surface and broke off on its 72nd landing. Never to fly again, NASA declared the end of Ingenuity’s mission on Jan. 25, 2024.

NASA describes Ingenuity as the first aircraft to achieve powered, controlled flight on another planet, and gives a final tally of 128.8 minutes of flight over a distance of 10.5 miles at altitudes up to 78.7 feet.

I’ve been fascinated by aircraft and space travel all my life, and Ingenuity ticked both those boxes. Even as a preteen, my younger sister Margaret once depicted me in a hand-drawn image as an airplane with a face and wings. My parents and siblings simply accepted this as part of my character.

OK, so I was a bit obsessed, but who among us hasn’t at least dreamt of flying? In one recurring dream, I was able, with great effort, to claw my way into the air with my hands and arms. Waking up to find that the air is way too thin to support my weight always came as a disappointment.

Ingenuity faced an equivalent challenge in the thin Martian air, which is less than 1% as dense as at sea level here on Earth — not a lot of mass to work with. Hurricane force winds on Mars would feel like a breeze on Earth.

In the 2015 science fiction adventure, “The Martian,” Matt Damon is stranded as a result of the chaos unleashed by a sudden dust storm. Director Ridley Scott has defended this wild misrepresentation as a dramatic plot device — an unfortunate choice for a movie that was otherwise praised for a more-accurate-than-usual portrayal. To my eye, it still made Mars appear far more attractive than it really is.

Growing up, I was greatly entertained making paper airplanes. Through trial and error, I learned basic aerodynamics, making adjustments until my creation glided in the desired way. These creations would have “landed” rather abruptly on Mars despite it gravity only 38% as strong as Earth’s.

A powerful catapult might give a paper airplane the airspeed needed for lift in the thin Martian air. Those pull-string plastic disk helicopters I used to love might take off if you could spin them at thousands of RPMs.

Engineers kept Ingenuity’s weight down to 4lbs, but its two four-foot long counter-rotating blades still had to spin over 2500 times per minute to produce enough lift to get off the ground. At 1.2 ounces each, these blades are lightweight marvels made of foam in carbon-fiber shells.

It might be tempting to compare operations on Mars to those on our moon, but the greater distances make it orders of magnitude harder. Depending where Mars in its orbit is in relation to Earth, radio communications at the speed of light have a one-way delay of anywhere from three to 22 minutes, so like the rovers, Ingenuity had to make real-time decisions autonomously.

Ingenuity’s autonomous navigation appears to have been confused by a somewhat featureless dune area, causing the accident that damaged the blades, and ending Ingenuity’s historic run.

Perseverance will continue its robotic search for evidence that life could have survived around Jezero crater sometime in the past, although I’d prefer it find the biosignatures — signs of possible past microbial life — it also seeks.

In a poetic turn of events, Ingenuity’s success has prompted plans for flying machines to gather the samples Perseverance has collected and stashed for a possible future sample return mission. These will replace the previously envisioned small rovers.

Although we may have seen the last of the little helicopter that could, there is a good chance it will show up as a few pixels in future images from the Mars Reconaisance Orbiter, which has been documenting the surface in exquisite detail since 2006.

Find rise and set times for the sun and moon, and follow ever-changing celestial highlights in the Skywatch section of the Weather Almanac in The Republican and Sunday Republican.

Patrick Rowan has written Skywatch for The Republican since 1987 and has been a Weather Almanac contributor since the mid 1990s. A native of Long Island, Rowan graduated from Northampton High School, studied astronomy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the 1970s and was a research assistant for the Five College Radio Astronomy Observatory. From 1981 to 1994, Rowan worked at the Springfield Science Museum’s Seymour Planetarium, most of that time as planetarium manager. Rowan lives in the Florence section of Northampton with his wife, Clara, and their cats, Eli and Milo.