The critically-endangered North Atlantic right whale population might be starting to level off after years of decline, but researchers said human activities still present significant ongoing threats to the species.

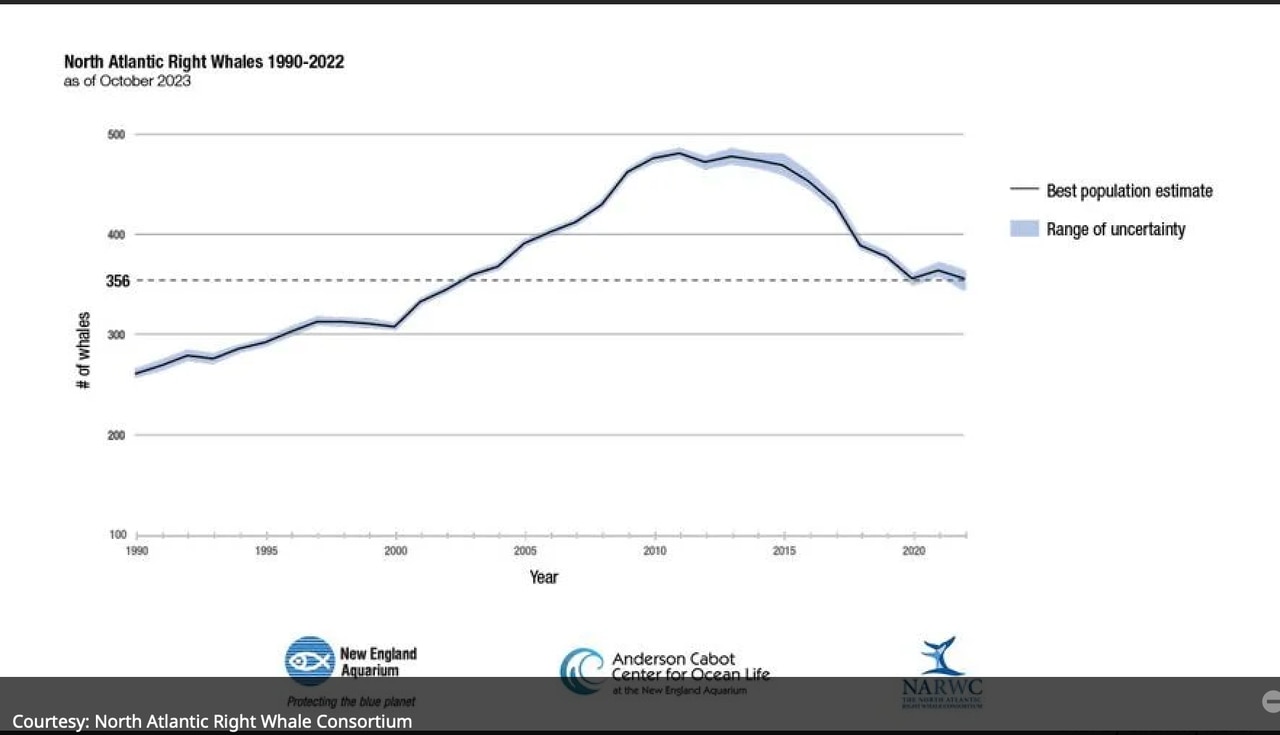

At its annual meeting this week in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium plans to release a new report estimating approximately 356 right whales in 2022 (range from 346 to 363) down from an estimated 364 in 2021 (range from 360 to 369).

The report also recalculated population estimates going back to 1990, and the consortium said the updated data show an “equal number of animals being born into the population as are being killed.” The species had an estimated 481 whales in 2011.

“While certainly more encouraging than a continued decline, the ‘flattening’ of the population estimate indicates that human activities are killing as many whales as are being born into the population, creating an untenable burden on the species,” Heather Pettis, a research scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium and the executive administrator of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, said.

(Courtesy: North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium/State House News Service)

Officials with the consortium said that while the overall population might be leveling off, there are concerns about the number of right whale calves being born. There were just 11 calves born this spring, fewer than the previous two years (18 in 2021 and 15 in 2022) and well short of the average of 24 calves per year from the 2000s.

Right whales got their name, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said, “from being the ‘right’ whales to hunt because they floated when they were killed.” Nantucket and New Bedford thrived as whaling ports in the 18th and 19th centuries, but the expeditions that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution severely depleted whale populations. Northern right whales have been listed as endangered since 1970.

Now as New Bedford and other former New England whaling ports aim for revitalization through the offshore wind industry, the industry faced headwinds from two federal lawsuits that focus on the protection of endangered species like the North Atlantic right whale and commercial fishing interests. A federal judge dismissed both cases, but the organization Nantucket Residents Against Turbines recently appealed its case to the U.S. Court of Appeals. That case is in its early stages, with the two sides jockeying over the amount of time to file initial briefs.

The first power from offshore wind generation is expected to be delivered onto the regional power grid by the end of this year. The state and country’s first utility-scale offshore wind farm, Vineyard Wind 1, was expected to begin delivering cleaner power this month, but project officials said last week when they announced completed construction of the project’s first of 62 turbines that the first electrons should flow onto this grid “this year.” The project has completely installed one of its planned 62 turbines.

The New England Aquarium said its analysis has detected 32 human-caused injuries to right whales so far in 2023, including six fishing gear entanglements with attached gear, 24 entanglement injuries (with no attached gear), and two vessel strikes.

Scott Kraus, chair of the consortium, said the rates at which right whales are injured and killed by humans are alarming.

“Until we implement strategies that eliminate injuries and deaths, and promote right whale health, this species will continue to struggle,” he said.

Last week, the ocean conservation organization Oceana released a report that showed most boats speed through the slow zones that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration establishes to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whales.

The report analyzed boat speeds from November 2020 through July 2022 in slow zones established by NOAA along the East Coast and found that 84 percent of boats sped through mandatory slow zones and 82 percent of boats sped through voluntary slow zones.