In recent years, Korean culture has been on a meteoric rise worldwide, whether in the form of music, TV shows, films, fashion and more — it’s a phenomenon known as “The Korean Wave,” or “Hallyu,” in its native Korean.

It might not take long for many to think of examples of South Korean culture going mainstream — from viral K-pop music video sensation “Gangnam Style” by artist Psy, life-or-death drama “Squid Game” on Netflix, or 2020 Best Picture winner “Parasite” at the Oscars, to name a few.

One exhibit, currently halfway through its run — it closes July 28 — at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (MFA), seeks to encapsulate the country’s catapulting pop culture ascent featuring about 250 authentic items, artworks and memorabilia from cultural touchstones in Korean history.

At “Hallyu! The Korean Wave,” curator Christina Yu Yu, chair of Asian Arts at the MFA, seeks to tell the broader story of how South Korea became the economic and cultural powerhouse the world knows it as today.

For its curator, it’s a story of how the country drew on its cultural and historical legacy coupled with its constant reinvention and innovation, to create something wholly Korean, yet influenced and shaped by both Western and Eastern forces around it.

“There’s this continuation of this culture, of this value system,” Yu Yu said. “So I think it’s very important to present here basically just to show that the phenomenon of ‘Hallyu’ did not come out of nowhere. It actually [took] a lot of time to build it up.”

A temporary exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston showcases how Korean culture has made a growing global impact.Chris McLaughlin

How modern history shaped ‘The Korean Wave’

The Korean peninsula was once an independent kingdom under the Joseon dynasty — and later the Korean Empire — until Japan colonized the land for decades until the end of World War II, Yu Yu explained.

Later ravaged by war in the mid-20th century, divided Korea stood, and remains, in two halves — the Western-aligned South, and Chinese and Russian-aligned North. From this divergence, South Korea went through a period of change, emerging from what was once a military dictatorship to a fully fledged democratic republic.

South Korea’s early embrace of technological innovation and the rise of “chaebols,” or large family-owned business conglomerates such as LG, Samsung and Hyundai — later coupled with the computers and internet — helped the country propel itself onto the global stage, made all the more significant by its hosting of the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul.

Mobile devices including cell phones and an MP3 player from Korean companies on display at the “Hallyu” exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.Chris McLaughlin

Yu Yu added artists like Nam June Paik, whose Olympic broadcast “Wrap Around the World,” is an early example of South Korea “using technology as a tool for you, as a language for you, to really show yourself to the world” — something which would carry on into the The Korean Wave.

“A recurring theme is really how today’s creatives constantly have this reference to Korea’s tradition and its history,” Yu Yu said. “Either to really embrace it and then use it very at ease, you know make it as one of their own language and show it very proudly, or sometimes maybe not at ease.”

Yu Yu said traditional values such as humility and respect for elders often clash with the fast-paced capitalistic wants and desires of today’s South Korean society. She said artists are nevertheless influenced by these values, but sometimes purposefully run toward or counter to them as a result.

Clothing worn by K-pop idols at the “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.Chris McLaughlin

K-pop at its core, Korean culture goes global

The first thing guests see at “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” are multi-colored screens showcasing “Gangnam Style,” the viral music video sensation viewed billions of times online since its debut in 2012. It is regarded as a breakthrough moment in “Hallyu.”

The MFA exhibit features a mannequin made to resemble Psy doing the song’s iconic dance pose and wearing a pink suit jacket worn by the singer himself in the music video.

The district referenced in the song, Gangnam, is a trendy and upscale part of the South Korean capital. Yu Yu explained how half-a-century ago, Gangnam was agricultural land where gleaming glass skyscrapers now stand. She added it is symbolic of how Seoul, and more widely South Korea, has changed since then.

Entering the central artery of the exhibition space is an orange-colored room with a double-decker platform full of glitzy music video couture, while hits from bands such as BTS and BLACKPINK play overhead. The room pays homage to Korea’s music traditions of both past and present, particularly the starpower of K-pop.

Yu Yu said for devout K-pop fans — or “stans” as they are commonly known online — many are able to identify the outfits presented according to the particular band, idol, or music video.

A temporary exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston showcases how Korean culture has made a growing global impact.Chris McLaughlin

Fan participation and interaction with K-pop idols is a core tenet of the music’s success, according to Yu Yu, saying it gives these fans greater agency and deeper connection to their favorite music artists.

She added that the K-pop industry uses South Korea’s same method of leveraging digital technology and social media as a tool to grow its audience and connect to people.

Part of how Korea is so tapped in technologically is government investment following a financial crisis in 1997, Yu Yu said. The crisis pivoted South Korea deeper into technological advancement, so much so, that it was one of the first countries where the vast majority of households had home internet, she said.

Years later, that trickle-down effect has caused young South Koreans to be particularly digital and tech savvy, according to Yu Yu.

Screens in the music section even depict the world’s first virtual K-pop idol group, Yu Yu said. The band is comprised entirely of AI-generated members which appear startlingly realistic to an untrained eye. Yu Yu added the virtual group emerged during the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, when in-person events were largely shuttered.

A lightstick used by K-pop fans to interact with and support their favorite music artists during concerts.Chris McLaughlin

At the rear of the exhibit, a wall displays dozens of “lightsticks,” or batons with glowing light tips. Concert-going K-pop fans show off their support for artists by personalizing and programming these digitized wands with their smart phones, Yu Yu explained.

The lightsticks can glow in specific colors and patterns to match songs’ rhythms, Yu Yu said, thereby adding to the fan-idol connection and experience when together in concert.

And for those who want to get their K-pop groove on, the “Hallyu” exhibit also features a music video dance training simulator with three levels of difficulty.

Participants learn from a digital instructor and have their dance moves recorded. The recordings are then compiled into a synchronized digital dance display projected in the space for all to see.

The idea was to incorporate guests into the K-pop fandom in a new, and literal, way, Yu Yu said.

Mannequins don costumes of guards and players from the hit Korean Netflix series “Squid Game.”Chris McLaughlin

South Korea on the screen and in style

Two tales of economic inequality and the extent one will go to escape poverty and enrich themselves — the TV series “Squid Game” on Netflix and the movie “Parasite” from director Bong Joon-ho — are two of the biggest visual media to emerge from South Korea in the past five years.

At the “Hallyu” exhibit, guests can get up close to costumed mannequins in the iconic teal green tracksuits of players and salmon pink jumpsuits of guards seen in the show. The series revolves around hundreds of players in a life-or-death competition of high stakes children’s games to win a life-altering cash prize.

Additionally, the exhibition space features a replica of the basement-level bathroom from the home of the impoverished Kim family in “Parasite,” who in the film deceive the wealthy Park family to slowly infiltrate their high-end home and lives, and in turn root out obstacles to their upward mobility.

However, South Korea’s on-screen growth is not limited to just eye-catching, big name TV shows and movies widely known to Western audiences.

A recreation of the bathroom of the Kim family from Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s Academy Award-winning film “Parasite,” which won “Best Picture” in 2020.Chris McLaughlin

Yu Yu said the earliest portions of “The Korean Wave” began in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, primarily with the embrace of K-dramas in East Asia.

She pointed to TV shows like “Winter Sonata,” a romantic comedy, which took off in Japan and developed a large female fanbase, cementing it as a “cultural sensation.”

Yu Yu said the popularity of the show even helped to bridge divides between Korea and Japan dating back to Japan’s colonization of the peninsula, with degrees of unease between the two countries persisting to this day due to this shared history.

“Because of this particular TV drama, it actually dramatically changed how some Japanese people see Koreans,” Yu Yu said. “When we talk about soft power, this is exactly what it is.”

The TV and cinema section also delves into the relationship between North and South Korea, showing off media like “Crash Landing on You” — a TV series about a South Korean woman who inadvertently paraglides into North Korea and develops a romantic relationship with a North Korean officer.

A framed jersey in the exhibit also shows the remaining ties between the two Koreas, despite their longstanding division and ongoing tensions.

A women’s hockey jersey showing a unified Korea from the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics and signed by both South and North Korean athletes who competed together on the same team for the games.Chris McLaughlin

At the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics, North and South Korean women’s ice hockey players joined forces as a unified Korean team for the first time, Yu Yu said. The jersey, signed by athletes from both sides, depicts an image of the Korean peninsula undivided without the labels of North or South.

Yu Yu said talk of North Korea in South Korea is often “very rigid,” but examples like these help to soften the perception between North and South Koreans, who despite a shared language, culture and history, are almost never able to openly communicate or meet one another.

One cultural item that transcends the North-South divide is “hanbok,” the traditional Korean clothing. Perhaps best exemplified by the long and voluminous dresses for women, they are typically paired with a top jacket and straps to secure the outfit.

A “hanbok” traditional Korean cultural dress in a glass case next to a painting showing Korean women dressed in “hanbok” at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.Chris McLaughlin

While perceived as “old-fashioned” in modern day South Korea, Yu Yu said this type of dress was once worn daily by Koreans centuries ago and is still worn to celebrate special occasions.

Fashion designers like Lee Young-hee, according to Yu Yu, have worked to reinterpret hanbok for more modern sensibilities in recent decades while also helping to spread recognition of the traditional garments.

“I think for a lot of countries with long histories like this, what happened hundreds of years ago is always an inspiration for today’s creatives,” Yu Yu said. “And there are many different ways of how to interpret that long history. It’s almost like it’s in your consciousness no matter [whether] you know it or not. It’s a part of you.”

- Read more: Chef Irene Li talks dumplings, James Beard Award, as food business Mei Mei turns 10 with new growth

A historic porcelain “moon jar” owned by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston on display in the “Hallyu” exhibit. The moon jar is a symbol of Korea.Chris McLaughlin

Presenting ‘Hallyu’ for American and local audiences

When the exhibit, which originated at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, came to Boston this spring, Yu Yu said the MFA sought to “recontextualize” it with parts of the museum’s own sizable Korean art collection.

A porcelain “moon jar” on display is considered a “visual icon of Korea,” Yu Yu said. According to her, moon jars came about in the 18th and 19th centuries and were utilitarian objects used to store food and liquids. One of the notable aspects of moon jars is their imperfections in shape and on their surfaces.

Yu Yu said it was chosen as a symbol of the country due to its simple shape, minimalist sensibilities and its ability to signal the “humble origins” and “resilience” of Korea.

Other MFA-owned art on display includes historic 19th century photos from the Joseon dynasty taken by a Bostonian photographer and a paneled screen depicting the eight Confucian virtues.

The MFA also incorporated pieces by local and Korean-American artists into “Hallyu,” a key difference from its debut in the UK.

One piece called “Lotto (Sweet Child of Mine)” by Boston-based artist Timothy Hyunsoo Lee, incorporates photos of Lee’s childhood in Korea transferred onto foil plates with gold leaf meant to resemble lottery tickets.

“Lotto (Sweet Child of Mine)” by Timothy Hyunsoo Lee. The artwork is a series of 30 aluminum plates covered in gold leaf showing images of Lee’s family on display at the “Hallyu” exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.Chris McLaughlin

- Read more: ‘Mind-bending’ Museum of Illusions to open at Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace later this year

“He said that when the family first came to America, he remembered his parents would buy lottery tickets on the weekends,” Yu Yu said. “And then you’d scratch the lottery tickets to see if you win or not. So it’s very symbolic. It’s almost like a very typical American dream story — like their hopes, their disappointments, their happiness, their sadness, all very symbolically wrapped in this one installation.”

Another piece by Korean-American artist Julia Kwon uses the handcraft of “bojagi,” taking strips of silk cloth to form a piece representing bar graphs of reports of anti-Asian hate crimes, which has risen in recent times. Yu Yu called it a “powerful piece.”

Yu Yu spoke about how the immigrant experience can often leave families and their children feeling torn between identities of never being Korean or American enough.

She added that the rise of “Hallyu” has helped some Korean-Americans feel prouder of their shared identities thanks to the world’s growing embrace of Korean culture.

In particular, Yu Yu said the “Hallyu” exhibit has helped to spur more young people and more Asian guests into the MFA, helping to foster a more inclusive space for all to enjoy.

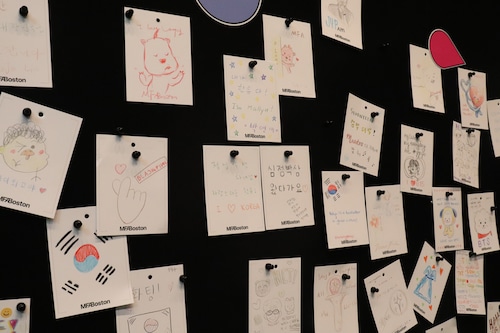

At the exit of the exhibit, guests can pin and leave messages on a wall as to what “Hallyu” means to them.

“Some are actually very neat,” Yu Yu said. “Some people will say, like, ‘We are an immigrant family who came here and a lot of stories resonated with our experience.’”

After its run in Boston, the “Hallyu” exhibit will travel to California where it will be shown at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, according to the MFA.

Notes left by guests after visiting the “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston expressing what “Hallyu” means to them.Chris McLaughlin