Early this year, a retired phys ed teacher left her ranch house in Easthampton and drove down the interstate to tell her story of clergy abuse.

It wasn’t Nancy A. Dunn’s first time before the Springfield Diocese’s review board, which meets in the red-brick Maguire Pastoral Center to hear allegations of clergy misconduct.

But it was her last.

The board later informed Dunn she needn’t have come back. Why? The diocese had already written her a six-figure check, she says she was told, to compensate her for a priest’s misconduct in the 1990s.

Dunn still had questions.

She wanted to know whether the Rev. Warren Savage had been held accountable, as the diocese had said he would, for engaging in a year-long sexual relationship with her nearly three decades ago. Savage remains in active ministry at Westfield State University.

“My intention was never to destroy this man, it was to hold them accountable,” Dunn said of Savage and the diocese. “I wanted accountability and transparency from the church.”

Today, Catholics worldwide continue to debate the circumstances under which sexual contact between priests and adults constitutes an abuse of power, even when it does not involve coercion. One new term is “vulnerable adult,” distinguishing that from decades of revelations of clergy abuse of children.

Bishops in dioceses like Springfield’s face a call to reexamine how they can better protect vulnerable people, following this year’s apostolic letter, “Vos Estis Lux Mundi (You are the Light of the World).” The message from Pope Francis took effect April 30 and expanded the definition of who should be seen as vulnerable, after revelations of abuse of adults. That step has been hailed as a breakthrough for adult survivors of misconduct, though some observers caution conflicts in its wording could blunt reform.

The case of Nancy Dunn presents local Catholic leaders with an opportunity to show how their thinking is evolving about a duty of protection.

Statements by the diocese, however, seem to show no eagerness to adopt a more expansive view of adults who deserve to be treated as survivors of clergy misconduct.

‘Struggling with my sexuality’

Dunn believes that when Savage began a sexual relationship with her, she was “vulnerable” – and used that word in her first written statement to the diocesan review board. The board upheld her claim in 1997 and recommended Savage “be removed from his priestly duties and parish work immediately.”

Evidence of her vulnerability lies in plain sight. Before entering into a sexual relationship with Savage, Dunn had been hospitalized for two weeks at the Brattleboro Retreat, a psychiatric facility in Vermont. “I was struggling with my sexuality,” she said. Dunn had thoughts of suicide.

Nancy Dunn stands in front of the former Notre Dame Church and rectory on East Main Street in North Adams. (Gillian Jones / The Berkshire Eagle)Gillian Jones

As a high school student, she had told her parish priest, the Rev. Homer Gosselin, she felt attracted to women. She recalls the priest telling her it was OK to have such feelings, but never to act on them.

In her early 30s, Dunn met Savage, newly assigned by the Most Rev. Thomas Dupre, the Springfield bishop at the time, to oversee a consolidation of parishes in the northern Berkshires.

Dunn’s psychotherapist, who she saw twice a week, had recently died. She said she asked Savage for a counseling referral, wanting to reconcile her sexual orientation with her deep faith and ongoing service to Notre Dame du Sacre-Coeur, her childhood parish in North Adams.

“It troubled me, as a Catholic,” she said of her feelings for women. She said Savage volunteered his counsel. “He said, ‘You don’t need a therapist, you have me.’”

In November 1995, Dunn says Savage initiated a sexual relationship with her during what she viewed as a pastoral counseling session. Savage disputes that he was counseling her. It was Dunn’s first sexual relationship with a man.

Dunn believed at the time Savage brought a divine message about her sexuality. “I thought Warren was God,” she said. “He said my sexuality needed to be integrated. I took it to mean I needed to have sexual experiences with him.”

Later, Dunn saw what she experienced as “spiritual rape.”

“Once, when I questioned him about why this happened, he goes, ‘I chose you.’ He made me feel like the chosen one. I know some people are going to be like, ‘How dumb are you?’ But I was vulnerable. I had just lost a therapist. I take responsibility for my role in this, but I was a vulnerable adult. I struggled with being lesbian. He made me feel special. And then I thought, ‘Maybe I’m not gay.’”

‘Major setback’

Nancy Knudsen, a Northampton psychotherapist who directs the Couple and Family Institute of New England, has been counseling Dunn for 14 years. Knudsen said her client has spoken clearly about having been in a counseling relationship with Savage.

“This has flavored Nancy’s entire life,” Knudsen said in an interview. “It was a major setback and left a very, very deep scar, because she thought she was loved and that this love was a message from God. The sense of betrayal was enormous.”

Patricia P. Martin, Ph.D., a licensed clinical psychologist based in Longmeadow, was a member of the diocesan review board that first heard Dunn’s account. Martin said ethics rules prevent her from speaking about how the committee handled Dunn’s case, but offered a professional opinion on the dynamics of cases involving clergy.

“In cases of sexual abuse by priests with parishioners, there is an imbalance of power,” she said. “This disparity of power and spiritual authority can be used as a means of coercing sexual activity.”

“This abuse is exacerbated if the person is a ‘vulnerable person,’ such as someone with a past or present mental health condition, who puts trust in the person of authority,” Martin said.

Looking back, Martin feels this would have been true for Dunn. “The sexual abuse of power and control is especially egregious if the survivor has been in any type of spiritual counseling relationship with the perpetrator. This poor woman, she was so naive about any of this.”

Given the passage of years, Dunn’s mental state at the time was perhaps best recorded in notes taken by a therapist she saw just weeks after halting contact with Savage.

The Rev. Warren Savage outside the Albert and Amelia Ferst Interfaith Center at Westfield State University in 2020. “To my great regret, I entered into an inappropriate consensual relationship with a 35-year-old woman … almost three decades ago,” he said in a written statement. (Don Treeger / The Republican)

In a July 1997 report to the diocesean review board, Carla Brennan, M.Ed., said Dunn had come to her in early October 1996 “extremely agitated, confused and distraught [with] major symptoms of anxiety and depression. She was disillusioned, feeling hopelessness and despair and had lost her spiritual faith.”

Brennan’s memo, a copy of which Dunn provided to The Republican, includes Dunn’s statement that her sexual contact with Savage arose from a counseling relationship.

“She revealed to him, within the assumed safety of the spiritual counseling session, her deepest insecurities, her wounds, her most private desires and needs and he used that knowledge to take advantage of her vulnerability and initiate inappropriate contact to satisfy his emotional and sexual needs,” Brennan wrote.

Diocese: Case doesn’t qualify

Though its review board concluded in 1997 that Dunn had been the target of “sexual exploitation,” the diocese maintains she does not qualify as a “vulnerable adult.”

“At no point, neither when the complaint was first received nor during subsequent reviews, was the individual deemed a vulnerable adult based on civil or canon law,” said Carolee McGrath, the diocese’s media relations manager.

When asked by The Republican how that could be, given the review board’s finding of sexual exploitation, a spokeswoman cited Catholic “moral teaching” that uses a narrow definition.

“Sexual exploitation covers any sexual conduct outside of marriage, which is a sacrament,” McGrath said in a follow-up statement.

This year, Pope Francis approved church law that has led to competing definitions of “vulnerable adult.” Here in Massachusetts, Cardinal Séan O’Malley of Boston has long advocated for an expansion of the definition of vulnerability. In November 2018, he told a conference of U.S. bishops that “we need to extend [the definition] to adults who can be the victims of abuse of power.”

This year’s “Vos estis” letter from the pope defines a vulnerable adult as “any person in a state of infirmity, physical or mental deficiency, or deprivation of personal liberty which, in fact, even occasionally, limits their ability to understand or to want or otherwise resist the offense.”

It falls to bishops to interpret and apply that definition.

The Springfield diocese says a committee is reviewing policies related to adult survivors of abuse. “When they complete their work, updates with any new information or policies will be made to the website,” McGrath said.

Knudsen, Dunn’s Northampton therapist, notes that her client had been hospitalized before meeting Savage and was not in a healthy state of mind.

“She was highly distraught about her sexuality and went to the priest with that in mind, looking for a counseling referral,” Knudsen said, and was in a state that left her unlikely to “resist the offense.”

“There is a power dynamic between a client and therapist which makes the client particularly vulnerable,” she said, speaking in general of the counseling field. “This was a powerful adult and a representative of the church. She was a lesbian woman in great conflict about her sexuality. This made her vulnerable.”

Like the diocese, Savage dismisses the idea that Dunn was a “vulnerable adult.”

While Savage declined to be interviewed on the record about his relationship with Dunn, he met for two hours with a reporter for The Republican at a Starbucks in Westfield and spoke with pride of his years of work on behalf of Catholics in Western Massachusetts.

In response to written questions, Savage provided a short statement: “To my great regret, I entered into an inappropriate consensual relationship with a 35-year-old woman – who was never in pastoral counseling with me – almost three decades ago.”

“Since that time, I have been held appropriately accountable, always maintained proper boundaries, and note that the new ‘vulnerable person’ standard is not retroactive,” he wrote. “Even if it was, this situation would not meet that standard.”

‘Expressed remorse’

A year ago this week, Savage met with Dunn at her therapist’s Northampton office and expressed remorse over his behavior in the 1990s.

It wasn’t his first apology. In a letter to Dunn on Oct. 16, 1996, he had taken responsibility; she kept that letter and shared it while recounting her story.

In a small, cursive hand, Savage wrote that he had become “more aware of the irreparable damage that I have done to you since November ‘95. … I am sorry and ashamed of the way I have treated you. … The bottom line is that I have messed up your life, which means I must pay a heavy price for this indignation.”

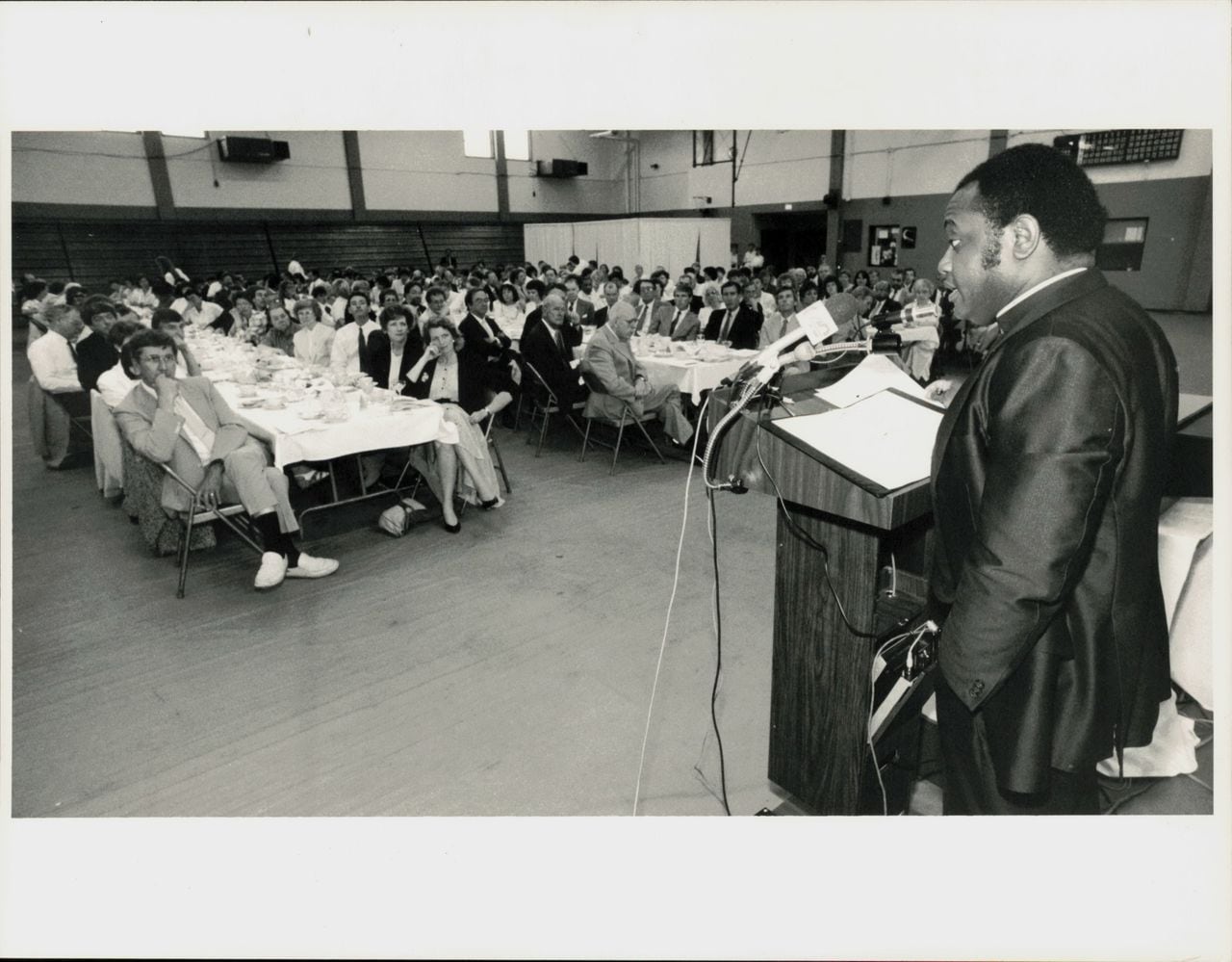

The Rev. Warren Savage, of Holy Family Church in Springfield, speaks in 2000 about AIDS at a breakfast event at the Springfield’s Boys’ Club.The Republican

The Republican spoke with three people familiar with Savage’s ministry today. All said that regardless of what happened in the 1990s, Savage is an exemplary priest worthy of public trust.

“He made a mistake and took the consequences,” said Sister Mary McGeer, who has known Savage for more than 40 years. “No one’s perfect. This man has spent his whole life doing good for everyone. He’s always come through.”

A Westfield parishioner wrote the Most Rev. William D. Byrne in 2021 to praise Savage’s current work at Westfield State University’s interfaith center, where he hears confessions and presides over a Sunday Mass. “He is on the front line, an army of one, who is doing God’s work,” wrote Jack Kurty. “One conversation, one phone call, one smile at a time. … I have never seen a better example of the advice that we should ‘practice what we preach.’”

Nancy Sterling, a spokeswoman for the Westfield State University Foundation, said officials learned of Savage’s history in 2021, after he’d been on the campus for seven years. The foundation provides a stipend to Savage for his work at the interfaith center.

“A detailed review of the matter was conducted,” Sterling said. It found Savage had complied with steps for his return to ministry, including required counseling. “Father Savage poses no threat whatsoever and is an asset to our campus ministry.”

The diocese notes that Savage admitted his wrongdoing “and followed all the steps required by the Misconduct Commission’s report.” That has included ongoing therapy and counseling. “Since then, no other complaints were brought forward. This was also verified by the Diocesan Review Board when they were presented [with] the case in 2022,” McGrath said, in response to questions.

“It was determined that he had fully complied with everything requested of him and that over the years he has provided valuable priestly ministry with no additional complaints of inappropriate behavior,” McGrath said. “Clearly, there is deep hurt that remains.”

The diocese reached a financial settlement with Dunn on May 31, 2022. Of the total sum, the settlement specifies that a portion was allocated “as compensation to Ms. Dunn for personal physical injuries, and emotional distress and anguish resulting from such physical injuries that Ms. Dunn alleges she suffered on account of Fr. Savage’s sexually assaultive acts ….”

‘Important step’

Advocates for victims of clergy misconduct, even within the Catholic church, are pressing nationally for a wider understanding of harm, arguing that the needs of adults who endured inappropriate sexual conduct with clergy deserve to be addressed.

“This is a very important step in the right direction,” said the Rev. Thomas V. Berg, a Catholic moral theologian at Saint Joseph’s Seminary and College in Yonkers, New York, who has written extensively on the issue.

Berg believes decades of revelations about the clergy abuse of children has created a sense of fatigue – and the perception that priestly misconduct with adults is a lesser offense.

Beyond that, he and others say the high moral regard accorded to priests overrides any sense of equality between a priest and a parishioner who have sexual contact.

“It’s much more manipulative and it has much more of the nature of an abuse of power,” Berg said. “The difficult position is that priests who are sexually active normally will be exceedingly good at covering their steps and keeping this secret and probably manipulating their adult victims into keeping this quiet.”

In a recent article co-authored with Timothy G. Lock and Justin M. Anderson, Berg explored internal church debate in recent years over the meaning of “vulnerable adult” and who it covers, noting the pull, for some, of a narrow definition of mentally disabled people.

That persists even with this year’s “Vos estis” letter, Berg and his co-authors wrote in the essay, “Fully Equipped for Every Good Work,” published by the McGrath Institute for Church Life at Notre Dame University.

“Most advocates for adult victims of abuse have urged Church authorities to adopt a broader definition of vulnerable adult that reflects the dynamic by which predator priests gain leverage from the power differential existing between themselves and their adult victims to groom and manipulate them,” the essay says. “A new paragraph now added to canon 1395 recognizes this dynamic, referring to it as an abuse of authority and identifying it as a canonical crime in the context of sexual abuse.”

Stephen E. de Weger, a scholar at Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia, who studies clergy abuse, believes this year’s revision to what constitutes a vulnerable adult falls short, leaving Catholic leaders discretion not to act.

His dissertation research found that people in power in the Catholic church tend not to believe accounts by adult survivors. “Unless they came under the very narrow strictures of the Vatican’s definition of vulnerable adult,” he told The Republican, “the go-to choice of response is dismissal of the complaint.”

In a presentation last year at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, Canada, de Weger said the new definitions have some value, but are strangely vague.

“I am left wondering, why do such vagaries for such important documents, and for such a serious issue, still exist?” he asked his audience. “Is the church actually trying to avoid clarity, and if so, why?”

Catholics seek change

Catholics across the country are pushing for change. Since 2019, members of AwakeMilwaukee have been meeting to raise awareness about sexual abuse in the church and to find solutions and bring about healing.

Sara Larson, the nonprofit’s executive director, says the Catholic church in the U.S. must make a stronger commitment to protecting adults from clergy misconduct, guided by the Vatican’s action.

“Individual dioceses have been slow to embrace this understanding and implement the necessary changes,” she said.

Part of the problem, Larson said, is public ignorance about the risks that adults who are active in their faith can face, including “grooming” and what she termed “the power differentials [that] can make true consent impossible.”

Often, adults who speak up are blamed and their abusers never face consequences. “I speak every day to survivors who are deeply traumatized by not only their abuse, but also the callous response they have received from church leaders in the aftermath of that abuse,” Larson said.

Berg said the public is often not receptive to accounts of misconduct that targeted adults. “Fatigue is absolutely real. People don’t want to hear this news. There is a default in the minds of people – that you knew what you were doing and could have kept your clothes on.”

Question of consent

The diocese says today the sexual relationship between Savage and Dunn – while “inappropriate” and “a violation of the vows he took as a priest” – was consensual.

That is the same position that a former bishop, the Most Rev. Timothy A. McDonnell, took in a 2005 letter to Dunn, after she asked that year about consequences Savage faced. McDonnell told Dunn he reviewed her statements to the Misconduct Commission. “There was a follow-up that was appropriate for a situation involving two consenting adults, as was the case here. It was very much different from a situation with an adult and a child, as I know you understand.”

Berg, the priest at Saint Joseph’s Seminary and College, rejects the idea that a parishioner brought into a sexual relationship with a cleric can be said to have freely offered consent.

“That’s preposterous,” he said. “That’s brain dead.”

Berg grants that there can be consensual sex between a priest and an individual who is not a parishioner, depending on the circumstances, even though that violates the vow of celibacy. “In reality, far too many of these relationships are manipulative and the perpetrator uses the power differential in that relationship to gain sexual access,” he said.

Berg questions the Springfield diocese’s decision to pay a settlement to Dunn, given its stance. “You don’t ‘settle’ in the case of a consensual relationship,” he said. “This is what I find problematic.”

He also disputes the diocese’s definition of sexual exploitation as any contact outside marriage. “If [the review board] deemed the relationship exploitative, that means a power differential was in play. That lies at the heart of sexual abuse of any kind, which in the opinion of many of us renders a woman vulnerable,” Berg said. “So the conjunction of ‘consensual’ but ‘exploitative’ is highly questionable.”

Today, the diocese continues to describe the relationship as consensual. It says Savage admitted to behaving inappropriately and that the priest’s behavior, and fitness for the ministry, has been monitored through decades of outpatient counseling.

“The more they told me I was a consenting adult, the more pissed I got,” Dunn said.

de Weger, the scholar in Brisbane, Australia, calls the issue of consent a moot point.

“Priests are religious professionals, having the double whammy of power, religious and professional, two spiritually and socially pedestaled elements of such men,” he said after being briefed on Dunn’s case. “It is very easy for such powerful men to groom, bamboozle, seduce the other person into what they then think might be ‘consent.’”

“Mature consent is not just giving in to such pressure, it is consciously saying yes with an equal person under no pressure or confusion,” de Weger said. “Anyway, it doesn’t really matter in the end. The priest should not be having sex with his ‘children,’ his parishioners, his ‘clients,’ full stop. Most people don’t get this and for some reason some even seem happy enough to let the priest off the hook because they’re ‘lonely’ or something.”

But if they were doctors or lawyers, he notes, they’d be fired.

‘Church everything to me’

Dorothy Small, a lifelong Catholic who lives in Woodland, California, sued a Sacramento County diocese in 2017 after having twice reported that a priest groomed her for sex. Small received a $200,000 settlement in 2019. Now in her late 60s, she has left the church, she said in a phone interview. “The Catholic Church was everything to me.”

“They teach you that the priest is the mediator between man and God. They are seen as Christ personified,” she said. “He represents Jesus Christ. There is no higher power. You’re actually more vulnerable to a priest than you would be to an actual therapist. You hold nothing back.”

Dorothy Small, poses for a portrait in her hot tub in the backyard of her home in Woodland, Calif., in 2019. (AP Photo / Wong Maye-E)AP

Small was 60 when she says a priest visiting her home engaged her in sex. “Consent can only be had between two people of equal power,” she said. “Submission is not consent. They’re in your head. They’ve got you. You’re not in your rational mind.”

“What was most important was that I retain my voice,” Small said. “You learn to walk to your own truth. It’s worth making a stink out of it – that’s what it takes. If we don’t say anything, we’re complicit to evil that continues to be perpetrated. “

Dunn says she’s learned that lesson.

“It has not been easy to speak up or tell my truth,” she said. “I was very alone in this process for years, with the exception of my therapist.”

This fall, Dunn joined a program for adult survivors run by the group Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. After receiving training, she plans to create a new support group in western Massachusetts.

“Ever since I got involved in this, I became aware of how other victims have been treated. I’m appalled,” she said. “This will be my new life mission.”