Ann M. Murphy still counts the days.

Twenty-three years.

It’s now been a generation, enough time for her brother’s two children to have grown from little girls in kindergarten and nursery school into accomplished women, one an attorney and the other in her second year of medical school.

Sally Trant brims with pride as she talks about her brother’s two sons and how much they’ve accomplished in the past two decades. One is married, and the brothers live and pursue careers in Denver, far from their family’s East Coast roots.

Kevin Shea says it’s been a good year for his family. He welcomed his first grandchild, there were two graduations and his daughter’s wedding on July 27 brought together all 17 of the Shea family cousins in Kansas City. Those festivities were topped off by announcement that his sister’s son, Colin Creamer, will soon be a father.

One thing remains unchanged. The city of Westfield, hometown to three young people who perished at the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, the day terror struck America, never forgets its lost loved ones: Tara Kathleen Shea Creamer; Brian Joseph Murphy; and Daniel Patrick Trant.

Creamer was aboard American Airlines Flight 11, the first of the jetliners that hijackers crashed into the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. on that long ago morning. Murphy and Trant, both of whom worked for the financial firm of Cantor Fitzgerald, were on the 104th floor of the North Tower, unable to flee as the building collapsed just after 10.

Within a year, Westfield’s Irish club, the Sons of Erin, dedicated a memorial to the three, and each year since pauses on the anniversary to honor and remember them and the nearly 3,000 who died in the attacks in New York, at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., and in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Ann Murphy will be there on Wednesday. So, too, will Sally Trant, along with Brian Shea and Elizabeth Harris, two of the Shea siblings who still call Western Massachusetts home.

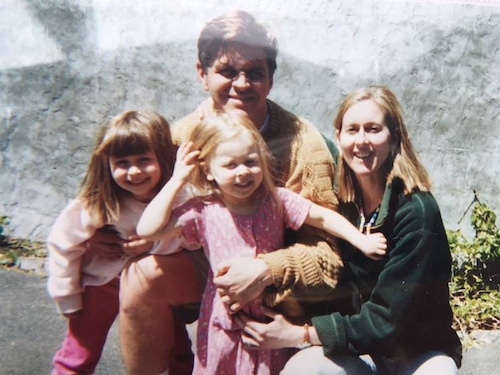

Judith Bram Murphy and Brian Joseph Murphy are seen here with their two daughters, Jessica Bram Murphy and Leila Nicole Murphy. The girls were ages 5 and 3 when their father was killed on Sept. 11, 2001, in the terror attack at the World Trade Center in New York City. He worked for Cantor Fitzgerald Securities. A native of Westfield, he was one three people killed at the trade center with ties to Westfield. (MURPHY FAMILY PHOTO)

Murphy isn’t looking forward to the media coverage that approaches. The image of the first jetliner hitting the trade center is forever gut-wrenching, she said: “I know where Brian was (then) so it brings it all back like it was 23 years ago.”

This anniversary comes against the backdrop of the announcement on July 31 that the government had reached an agreement in which Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the terror attacks, and his associates Walid Muhammad Salih Mubarak Bin Attash and Mustafa Ahmed Adam al Hawsawi would be spared the death penalty in exchange for pleading guilty. Within days, Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III revoked the agreement, saying the decision would rest with him.

“I have mixed feelings,” said Murphy. “Honestly, I think the death penalty would be a fitting punishment. They have admitted culpability and to organizing the plots to execute the terror attacks.”

She makes clear she speaks only for herself and thinks of the trauma endured by her father, who died in 2003, and her mother, who died in 2014. Her two nieces have been to Guantanamo and believe the treatment of the 9/11 prisoners there over the past decade has been “extremely inhumane,” said Murphy.

“I’m not sure I can convey that much empathy because I think about the trauma that was inflicted on our family and multiply it by almost 3,000 victims,” she said. “It’s not only the victims of that day, but all the first responders who have suffered as a result of their involvement in rescuing and recovering. If you multiply the effects of that on society, that evil should not go unrecognized. It has to be punished or others will continue to carry out such acts.”

Daniel P. Trant, who grew up in Westfield, was killed on Sept. 11, 2001 at the World Trade Center. He worked for Cantor Fitzgerald in the North Tower. (TRANT FAMILY PHOTO)

In the gated community where Sally Trant lives in Florida, she’s become friends with a retired New York City firefighter who endures the health effects of all he breathed in while working at Ground Zero. It is an ever-present reminder that there are many more victims than the almost 3,000 who died that day in 2001, she said.

“It seems like it was yesterday. Then I stop and think how long my dad’s been gone and it just doesn’t seem possible.” Their family patriarch, William T. Trant, who had survived being among the first of America’s wounded in the D-Day invasion of France in 1944, died less than a year after 9/11, his passing hastened, the family has said, by the tragedy of 2001.

All of the Trant siblings’ children, like her brother Dan’s, are now grown. Some were too little to have truly grasped what their uncle was like, Sally Trant said: “They see pictures of him. They know all about him, but it’s more learned memory.”

Trant was so pleased by the defense secretary’s revocation of the plea deal that she sent Austin a letter of appreciation. “I thanked him,” she said, “and added, just for the record, that while the attorneys said they contacted the families about this, that is not true; I don’t know of any family members who would agree to a plea deal. I think they deserve the death penalty.”

Trant is among family members of 9/11 victims who have kept pressure on the U.S. government via a lawsuit that accuses Saudi Arabia of being complicit for having aided some of the hijackers when they first arrived in the U.S.

“Lately, I am terrified something is going to happen again. Twenty-three years isn’t long enough for me to think it’s in the past,” Trant said. “For the life of me, I cannot understand how after all these years and every political party in power, we are protecting Saudi Arabia. …There is absolute evidence Saudi Arabia was behind this.”

Kevin Shea, the eldest of the six Shea children, credits his late father, James F. Shea, with guiding the family through the shock and grief of 9/11. In an interview on the 10th anniversary in 2011, the elder Shea said his mantra to comfort his family was simple: “There are more happy times in life than sad times. The sad times are the jolts and bolts. You take the cuts, but (I) think about the good times.”

Tara K. Shea Creamer, of Worcester, who grew up in Westfield, was a passenger aboard American Airlines Flight 11 on Sept. 11, 2001. (SHEA FAMILY PHOTO)The Republican file photo

Unknown to Jim Shea until after his daughter’s death, Tara Creamer had made a pact with her siblings that if anything happened to one of them, the others had to ensure their children would spend time with their cousins on a beach each summer, enjoying the same kind of family vacations they’d had as kids. He made certain that tradition continued, Kevin Shea said.

Thus, the wedding this summer of Kevin Shea’s daughter, Rylee, and how it united all 17 cousins carried immense meaning for the entire family. “As my dad would say, it’s the good times that are important, and there’s been plenty of good times. … You’re going to get hit. You take the bolts. It makes it even more important to double down on the good times.”

Kevin Shea is approaching his 62nd birthday, the same age his father was on 9/11. “How impossible that would sound if that had happened to me,” he said. “He was a great dad, a great leader of our family. He was pulling a big sled and we all reacted the way he reacted, (to) thank God for all you do have. You may scratch your head or not understand why (something) happens, but the older you get, there is more appreciation.”

There will be great appreciation among the Murphys, the Trants and the Sheas on Wednesday as their hometown remembers 9/11.

“God bless the city of Westfield for always doing it. I think it’s wonderful, and, as long as I am able, I’ll be there,” said Trant. “That’s what means something to me. That’s where I feel the love for Danny and Tara and Brian. It makes me feel good.”.

Added Murphy, “I think it’s a real testament to the community spirit of Westfield. They’ve gone out of their way to make sure we don’t forget … and to support the families, too, by providing that remembrance annually. For me, that really is Brian’s resting place.”

Said Shea, “The message to your readers is that the Sheas and our extended family are doing great. We’ll cry a little bit, but we’ll also be thankful that we came from a special place like Westfield that always remembers. Words cannot express what that means to us.”

Cynthia G. Simison is retired executive editor emerita of The Republican. She may be reached by email to csimison@repub.com .