April 20, 1945.

Adolf Hitler marked his 56th birthday inside a bunker in Berlin as Soviet artillery began bombarding the city, marking the beginning of the end for World War II in Europe.

In northern Italy, 26-year-old Army Capt. John Philip Serex was killed in action by the Nazis as the Allies entered the foothills of the Apennine Mountains in pursuit of retreating Axis forces who fled into the Po River valley.

“The turning point in the spring offensive came on 20 April, with both the Fifth and Eighth Armies in position to launch high-speed armored advances from the Apennines foothills toward the Po River crossings,” reads the Army’s historical account of the Po Valley campaign.

Word of Captain Serex’s death would not reach his hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts, until the afternoon of May 2, the same day that German forces surrendered in Italy and two days after Hitler had committed suicide.

One can only wonder if there was some solace in the news of the war’s end for Serex’s widowed mother, Bertha Serex, when she learned of her son’s death. She was sharing the family homestead at 327 Lincoln Ave. with her eldest son’s wife, Elizabeth “Betty” Taylor Serex, and the baby daughter he’d never know. The family patriarch, Paul Serex, a distinguished chemistry professor at the state college, had died in the spring of 1943 at the age of 52.

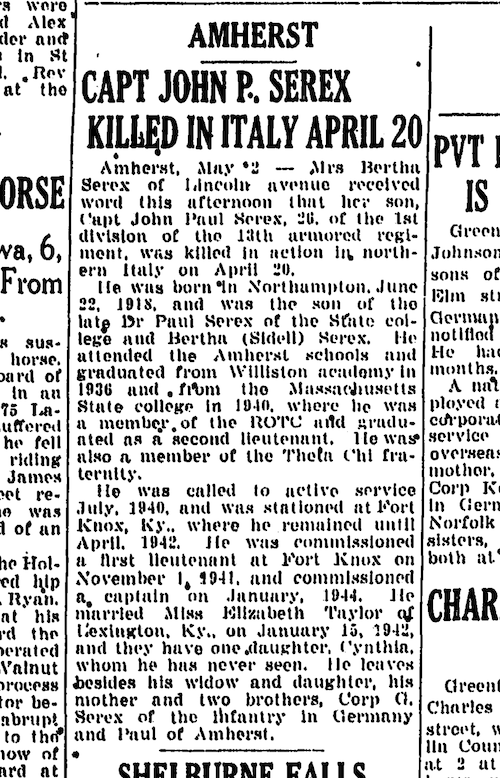

News of the captain’s death was reported in a story headlined, “Capt. John P. Serex Killed in Italy April 20,” on page 7 of the Springfield Republican of May 3, 1945. Next to it was reported the death in Germany on April 19 of Pvt. Norman Johnson, of Greenfield; the 18-year-old Johnson, the youngest of four siblings at war, was killed after only two months overseas. And, next to that was published news that Pvts. Ernest and Edwin Hartwell, of Greenfield, both prisoners of war, had been liberated in Germany, were in a repatriation center and would be headed home soon.

A clipping from the May 3, 1945 edition of the Springfield Republican. announcing that Capt. John P. Serex was killed in Italy during World War II.Third Party submitted

For John Serex, death came after nearly three years of combat duty with the 1st Armored Division’s 81st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squad. His unit had gone from the sands of the Tunisian desert in North Africa, to Sicily and then to the invasion of southern Italy at Anzio, onto the liberation of Rome and into the Apennine Mountains where he spent his final days.

He had been bound for military service since graduating from Williston Academy in 1936 and entering the Massachusetts State College that would one day become the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Serex completed cavalry instruction in the college’s Reserve Officer Training Corps and, after graduation in the spring of 1940, entered active duty that July. He headed to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he remained until April 1942.

It was in Kentucky that he met and married his wife, who was from Lexington; articles in the Springfield Republican show the couple visited Amherst following their wedding in January 1942. That September, their daughter, Cynthia, was born; the lieutenant was overseas at a base in Ireland in preparation for the invasion of north Africa, according to newspaper articles that chronicled his service.

Capt. John P. Serex was killed while serving in Italy during World War II. He is seen here in his Massachusetts State College yearbook photo from 1940.Third Party submitted

As Serex’s unit followed the path of war from Tunisia to Sicily and into mainland Italy over the course of the next two-and-half years, he earned a battlefield promotion to captain in early 1944. “As part of the 1st Armored Division, the 81st had more battlefield experience than any other American reconnaissance battalion or squadron,” according to historical documents archived at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

John P. Serex is buried in the Florence American Cemetery, Plot D, Row 14, Grave 4. It was there that I first came to know of him.

I visited the cemetery purely by chance with a group from Pioneer Valley Travel in Northampton on Nov. 12, 2022. It came near the end of a long day touring the city of Florence; our guide, having learned of our collective interest in World War II, arranged for a tour that included participation in the end-of-day, flag-lowering ceremony.

The Florence American Cemetery, maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission, is the final resting place for 4,392, whose graves are arrayed in symmetrical curved rows of a hillside on the 70-acre site. Another 1,409 missing in action are also memorialized at the cemetery.

Most died in the fighting that occurred after the capture of Rome in June 1944. Many, like Serex, were casualties of the heavy fighting in the Apennines in the weeks before the war’s end. Victory in Europe was observed on May 8, 1945.

I went in search of two gravesites that afternoon, one for any member of the famed Buffalo Soldiers so that I might share a photo with an acquaintance back home in Springfield who honors the legacy of the African-American troops that saw combat in World War II. I also wanted to find any soldier from Massachusetts so that I might pay homage to their service.

Capt. John P. Serex, 26, of Amherst, is buried at the Florence American Cemetery in Italy.Third Party submitted

Back on the tour bus as the sun set, my journey to get to know Captain Serex began thanks to the internet. What I first learned that evening left me yearning to find out more: There is a memorial stone to him alongside his parents’ graves in Spring Grove Cemetery in Northampton; my relatives, including my World War II veteran father, are buried nearby in the same cemetery. What were the odds of such a “small world” connection?

I’ve spent time over the past 18 months in search of information about the captain, learning what I could with the help of Ancestry, The Republican’s archives, military databases and other resources.

When the American Battle Monuments Commission was established in 1923, its mission was to oversee the cemeteries and memorials around the world that honor the service of members of the U.S. armed forces. Promised its first director, Gen. John Pershing, “Time will not dim the story of their deeds.”

Today, there are 26 American military cemeteries and 31 memorials, monuments and markers overseen by the commission. They commemorate the service of Americans during World Wars I and II; they are located in 17 foreign countries, the U.S. commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and the British dependency of Gibraltar. Four of the memorials are in the U.S.

The cemetery in Florence provided me my first firsthand glimpse of how we honor our World War II veterans in the lands where they fell; I hope one day to visit the cemetery at Normandy in France where those who fought alongside my father are buried and to chart his path across Europe with the 29th Division.

Until then and, on this Memorial Day, I pay tribute to the deeds of Capt. John P. Serex.

Cynthia G. Simison is retired executive editor emerita of The Republican. She may be reached by email to csimison@repub.com