In civil lawsuits where one party alleges that another party caused them harm negligently or intentionally the standards by which this can be proven are well established. Among these are whether the alleged wrong-doer went against the law, the policy governing their actions, established industry standards and practices, or good old common sense. Going against any of these standards, known as the standard of care, could result in a loss to the defendant and restoration to the plaintiff.

The common sense part is known as the “reasonable person” standard. What would most people do when confronted with the choice the defendant had to make? We understand, of course, that this can’t mean what the average citizen would do in cases where specialized knowledge is needed. For example, an eye surgeon being sued for an error made during surgery would not be judged by a survey of 100 random people coming out of Walmart asking “What would you do if, if you encountered a hemorrhagic occlusion of the retinal vasculitis during cataract an intraocular injection?” Obviously, the reasonable person in this scenario is a reasonable ophthalmologist. Nor could that same random group answer what they would do in determining what type of material would guarantee that a certain structure would bear up under various pressure and atmospheric conditions in a case alleging misfeasance by an engineer or architect.

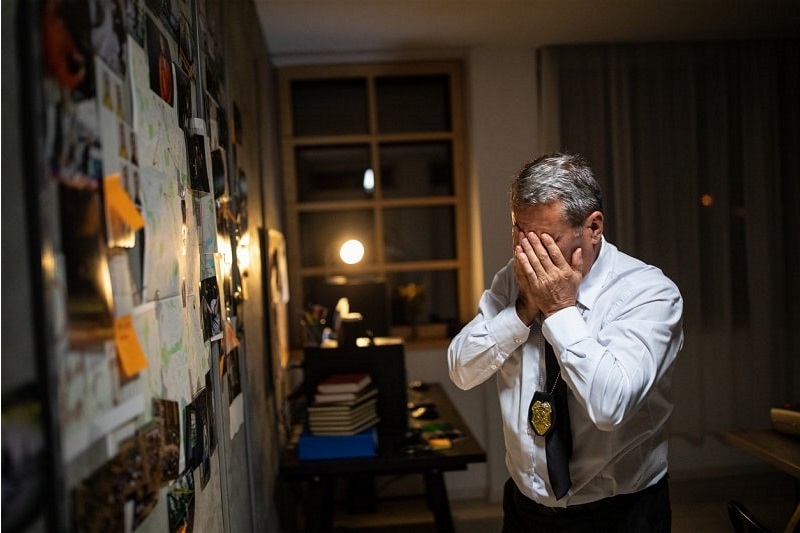

In the same way, if a police officer is being sued for the results of a decision they made, the questions would be about what law governed the situation, what the department policy and training were that governed such situations, and what a reasonable police officer would have or should have done.

Sometimes a situation encountered by a police officer is so unique that law, policy, and experience has not specifically addressed what the right response should be. It is for these situations that the courts have created an immunity, called qualified immunity, for police officers. Since an officer is obligated to take action as required by their legal responsibilities and professional ethics, they must engage in the situation with their best effort based on their experience and training. To facilitate those decisions, the law has allowed room for a bad outcome that resulted from the best decision the officer could make at the time.

Part of the anti-police elements of police reform is to remove qualified immunity from the law and some states have succeeded in doing so. This means that some cases that would normally be dismissed now must proceed to trial, often at a waste of the courts’ time and resources.

At trial on such a matter where the law and policy are undeveloped, the standard of care can default to the reasonable person standard. Establishing what a reasonable officer would have or should have done is a great challenge to defense attorneys because, as in the case of any profession, it is challenging for an ordinary juror – or judge or attorney for that matter – to understand what is required in making a professional judgment on a complex matter such as the use of deadly force in a rapidly changing emergency.

A recently noted study on police decision-making attempted to take into account all possible variables and found that there are over 50,000 individual factors that play into a police officer’s decision on a critical event. How is it possible for a person without police experience and training to understand the infinite complexity facing an officer’s decision? That’s not to say that we should, therefore, give so much leeway to officers that there is no accountability, but we must allow as much information as possible to be given to those making prosecutorial judgments, judicial declarations, and jury decisions so that the reasonable officer standard can be as fully understood as possible.

Complicating these factors are the biological limitations of an officer to be both consciously aware of all of these variables, and to have the facility to express them all in the documentation of the event. Reports are all that stand between the officer and the actors in the justice system who will judge the officer months or years after the event. Video footage may appear to be self-explanatory and witnesses may be objective in their perception of an event, but without the appropriate narrative and context, even this evidence can be misleading, especially in an adversarial proceeding.

This writer followed a case in Oklahoma where an officer was criminally charged after a shooting. I offered to comment publicly on the case, but the officer’s attorney felt that it might not be helpful and declined. During the officer’s trial, the judge would not allow a use of force expert to testify on the human performance realities of decision-making under stress, leaving the jury to rely on their own beliefs from a lifetime of watching television and movies to determine the reasonableness of the officer’s actions. They rendered what I believe a decision contrary to justice. Any officer who has been involved in a shooting incident will tell you that media portrayals, and even law enforcement training scenarios, not only fail to represent an actual event but can present contradictory information.

If only we could take Elvis’ advice in his song – before you accuse, criticize, and abuse, walk a mile in my shoes.