NEW YORK — On a recent Thursday afternoon, Antoine Balimr prepared to inject drugs. On a wall behind him, bold blue letters spelled out the mission of this unusual place.

“This site saves lives.”

Balimr sat at one of eight booths at OnPoint, a supervised injection site in Harlem. If he overdosed, people in the room stood ready to respond with an injection of naloxone — medication that can reverse an opioid overdose — and an oxygen tank to help restore breathing.

Balimr has been saved from overdose here. Between this site and a second location in Manhattan, the only programs of their kind in the country, OnPoint NYC staff report intervening in more than 1,200 overdoses over two years. No one has died there, they said.

Alsane Mezon, who works in the center, attributes the facility’s success to being able to administer naloxone seconds after staff notice someone experiencing an overdose. The room where people can use illegal drugs under supervision was added to the Harlem center two years ago, a place already been home to harm reduction services that includes a needle exchange.

People like Balimr bring their own substances. The center does not supply illegal drugs. Visitors can receive other services, like counseling and medical assessments.

The goal of the center is to reduce harm and keep people alive amid the opioid overdose epidemic. Advocates for this and other harm reduction approaches often say no one can recover from substance use disorder if they’re dead.

Sites like this one could open in Massachusetts if a proposed law before the Legislature passes.

Opioid overdose deaths in the state hit an all-time high last year. The Legislature is considering a measure that would authorize overdose prevention sites — also known as supervised consumption or supervised injection sites — through a 10-year pilot program.

Just a few hours away in New York City, the idea is a reality at two sites, the only authorized ones in the U.S.

Legal questions hang heavy, with federal authorities threatening to crack down on the New York sites. But so far, two years after opening the supervised consumption areas, they’re still operating.

Inside OnPoint NYC

In a busy neighborhood on 126th Street, OnPoint NYC operates in a red-brick, four-story building. There’s a deli next door and a preschool across the street.

The Harlem site opened its overdose prevention center in late November 2021. Previously under the name New York Harm Reduction Educators, the organization had been in the East Harlem area for more than 20 years, said OnPoint NYC’s executive director, Sam Rivera.

The same day in November 2021, the Washington Heights Corner Project opened a similar overdose prevention center. Both organizations merged into OnPoint NYC and continue to offer other harm reduction services, such as wound care, disease testing, and drug testing to determine how potent a sample is.

“We’ve been around two years now. And the impact is everything we expected and more,” Rivera said. “We’re keeping beautiful people alive.”

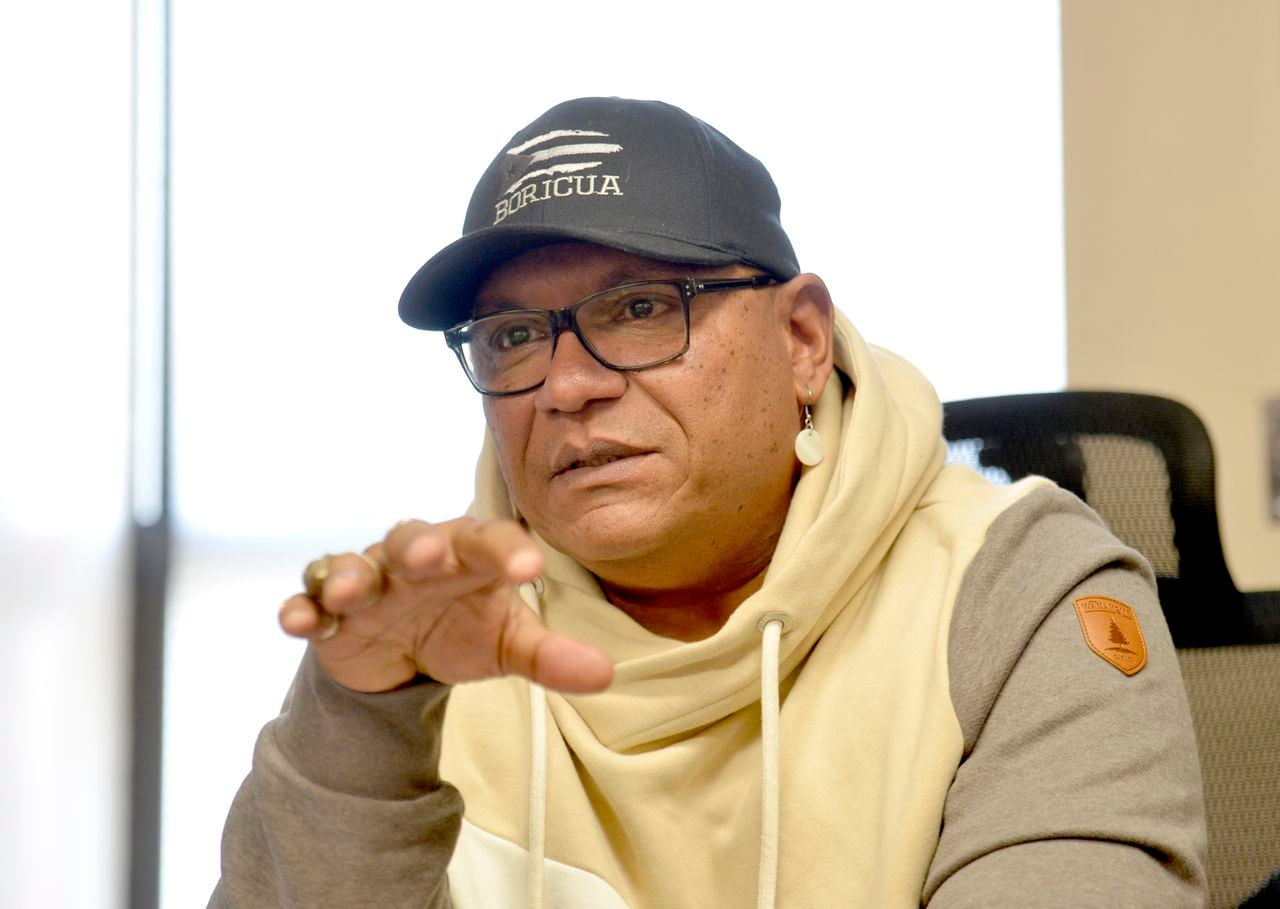

Sam Rivera is executive director of OnPoint NYC, a safe injection center on 126th Street, one of two centers in Manhattan where people can use drugs under the supervision of trained workers. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

The center’s intake room was bustling on a recent afternoon with dozens of people. Some were there to use drugs in a room under supervision. Others sought other services. There are showers, food, lockers to store belongings and a place to do laundry. People gathered watching TV.

Past the intake room, visitors arrive at the overdose prevention center. On a recent afternoon, Mezon and three others were there to respond in case of an overdose. When an overdose occurs, they use an injection of naloxone, Mezon said, rather than a nasal spray.

The vestibules in the consumption room at OnPoint NYC are where people can come and take drugs in a supervised area. OnPoint NYC is a safe injection site on 126th Street in New York City. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

The room has an area with clean supplies like syringes. “We try to educate them on safety,” said Mezon, who has worked at OnPoint for about two years and has responded to many overdoses.

“I get a lot of moms that call me and say ‘Thank you,’” she said.

Alsane Mezon, the “Responsible Person in Charge” in the consumption room of OnPoint NYC safe injection site, shows a tattoo on her arm, an image of the syringe most popular with IV drug users. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

On her forearm she wears a tattoo of the most popular syringe users opt for. It’s orange-capped and life-sized.

Staff have called ambulances a few times, Mezon said, but only when the center were closing and they needed to transfer care of a person who wanted medical attention.

Balimr sits at one of the eight booths facing a mirror, which helps staff monitor users. He showed lesions on his skin he attributes to xylazine, an animal tranquilizer that is being found more and more in the illegal opioid supply. He’s been getting help with his wounds at OnPoint and Mezon says he’s improving.

Two other people like Balimr were in the overdose prevention room that afternoon.

Elsewhere in the center, OnPoint employs case managers who can provide mental health resources and clinical services, like disease testing, wound care and medication-assisted treatment.

Susan Spratt is the associate director of clinical services at OnPoint NYC, a safe injection center on 126th Street, one of two centers in Manhattan where people can use drugs under the supervision of trained workers. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

“For a lot of people, we’re the only medical care they see,” said Susan Spratt, associate director of clinical services.

Medical staff help clients find longer-term care, Spratt said. That can include addiction treatment.

The center’s second floor houses a holistic health center. Music and the smell of essential oils wafted out from the room, as people stretched out on massage tables and others sat in chairs and received acupuncture. People can drop in for those free services.

Mauer Cruz of New York City gets an acupuncture treatment in his ear from a Holistic Team member during a visit to the OnPoint NYC center in Manhattan. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

Juan Cortez, program manager for holistic health, worked for New York Harm Reduction Educators before coming to OnPoint and has nearly 20 years of experience in the field.

When people think about a spa in New York, they picture wealthy people in SoHo, he said, sitting in his office wearing a baseball cap with a yin and yang symbol. “They don’t think about poor people in Harlem.”

Cortez said these resources offer another way to help people. “When we talk to people about trauma,” he said, “it’s a way to address it without saying a word.”

Outside center’s doors

Midday on the street outside, people offered thoughts about the program.

View of the street in front of the OnPoint NYC supervised injection site on 126th Street in New York City. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

Denzel Fell lives in East Harlem. “They’ve been saving people for years,” he said. “They’re the best.”

Wade Michaels does not use drugs, but has accessed some of the social services at the site.

Wade Michaels shares his views about the OnPoint NYC supervised injection site on 126th Street in New York City. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

“It’s a safe place for people,” he said. “I wish we had more safe places for people to go.”

Johnnie Jackson’s family lives across the street from the East Harlem center. When he first heard about the overdose prevention site, he thought it sounded great. But he’s since changed his mind.

Johnnie Jackson talks about the neighborhood outside the main entrance to the OnPoint NYC safe injection center on 126th Street, one of two centers in Manhattan where people can use drugs under the supervision of trained workers. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

“I appreciate what they do for people. It’s amazing … somewhere else,” Jackson said.

He took issue with its location across the street from a preschool, gesturing to a four-story, white building that’s home to the Graham School at Echo Park run by the Association to Benefit Children.

The site’s leaders make an effort to be a good neighbor, Gretchen Buchenholz, the school’s executive director told The New York Times.

A preschool on the left sits across the street from the OnPoint NYC safe injection site (yellow awning in the distance on the right) on 126th Street in Manhattan. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

Jackson thinks the site has made the neighborhood more dangerous. “It brings more drug dealers out in my community,” he said. “My kids ask questions.”

Crime has not increased in the two years since the overdose prevention centers opened at the OnPoint NYC sites, according to a study published last month in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Researchers at University of Pennsylvania, Brown University and the University of Connecticut analyzed 911 calls, nuisance complaints, crimes like burglary and assault, medical events, and arrests for drugs or weapons.

Another party opposed to the site is a top federal prosecutor.

Damian Williams, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, has said OnPoint NYC is operating in violation of state and federal laws.

“That is unacceptable,” he told The New York Times in August. “My office is prepared to exercise all options — including enforcement — if this situation does not change in short order.”

A so-called “crack house statue,” prohibits maintaining a space “for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.”

At least one state has authorized supervised injection sites. Rhode Island legalized a pilot program and an organization is planning to open a site in 2024.

Philadelphia nonprofit SafeHouse has been trying for years to open a program and faced legal challenges.

‘These are folks who … want to stay alive’

Rivera, OnPoint’s executive director, knows that plenty of people disapprove of the overdose prevention centers. He tells them the centers responded to public requests.

“You didn’t want people using drugs in your community. You didn’t want people dying in your community in the local bathrooms and parks,” he said. “You don’t want paraphernalia in the streets and in the kids’ parks. We just brought all those people in.”

“We’re coming up on 100,000 utilizations,” he said, referred to center visits. “What that means for two neighborhoods in New York, 100,000 times people would have used in their community (and instead) used inside with us.”

Three-quarters of people who used the centers in their first two months reported that if not for these locations, they would have used drugs in a public or semi-public place, researchers found in an analysis published in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

OnPoint lists a phone number on its website that people can call if they see syringe litter or public drug use. The center dispatches a team to clean up and tell the person using drugs they can come use at their site instead.

Sam Rivera is the executive director of OnPoint NYC, a safe injection center on 126th Street, one of two centers in Manhatten where people can use drugs under the supervision of trained workers. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 11/16/2023The Republican

Rivera often hears the objection that his program enables people to use drugs.

It’s a misconception, he says. “We’re working with folks who’ve been using drugs a very, very long time,” he said. “This isn’t a place where people learn to use drugs. These are folks who’ve been using and want to stay alive.”

Rivera has not used drugs, but relates to people who use the center because of other life experiences. When Rivera was younger, he went to prison. When his therapist asked why he went to prison, he answered that he was involved in organized crime.

This didn’t suffice, and she kept asking.

“Well, I got arrested,” he said. “No, no, why were you in prison,” he recalls her asking. And then he saw where she was headed.

“What happens to someone where they would put themselves in a position where they can die and then go to the penitentiary in New York?” he asked. “At the core of it was pain. It was trauma. … For a lot of people who use drugs, it is the same thing.”