HUNTERSVILLE, N.C. — Mark Maye chuckles after he drives past Bailey Middle School, where the boulder in front is painted in blue and yellow with Ted Lasso’s “BELIEVE.” When his son Drake was a student there, he didn’t need any signs.

Belief has never been an issue for the New England Patriots’ first-round pick.

On a similar ride through Huntersville over a decade ago, Mark remembered 9-year-old Drake sitting in the shotgun seat as he shuttled eldest brother Luke’s AAU carpool. Luke was in high school and kids his age had started getting attention in the college recruiting process, so Drake asked the carload of teenagers where they’d gotten offers from.

Luke’s teammates responded with a number of Division I schools, but mostly lower-tier ones. When they weren’t blue bloods like North Carolina or Kentucky, Drake repeated “awwww, what!?” At the end of the roll call, the 9-year-old turned around in his seat.

“Man, y’all need to step your game up,” Drake cracked.

Luke’s teammates all wondered the same thing:

Who the heck does this kid think he is? Just wait until he’s in our shoes.

While others were being courted by mid-majors, Luke had top-shelf suitors in pursuit. North Carolina’s Roy Williams came to the Maye household to have dinner with the family and make his pitch. Rather than being awed by the legendary coach, Drake put his own spin on the evening.

“He said, ‘Y’all watch. Coach Saban is going to be in our house at some point, and I’m gonna let y’all know that I told y’all when I was (this young). Coach Saban is going to be in our house soon,’” Luke recalled on a phone call from Japan.

Sure enough, Nick Saban wasn’t just on the Mayes’ front stoop a few years later, he was sneaking up the back staircase at Myers Park High School to get a glimpse of Drake playing basketball, too. Saban recruited him aggressively, and Drake initially committed to Alabama before flipping to North Carolina.

“For him to say that and make it reality was just the kind of confidence he had and the kind of person he really was,” Luke said.

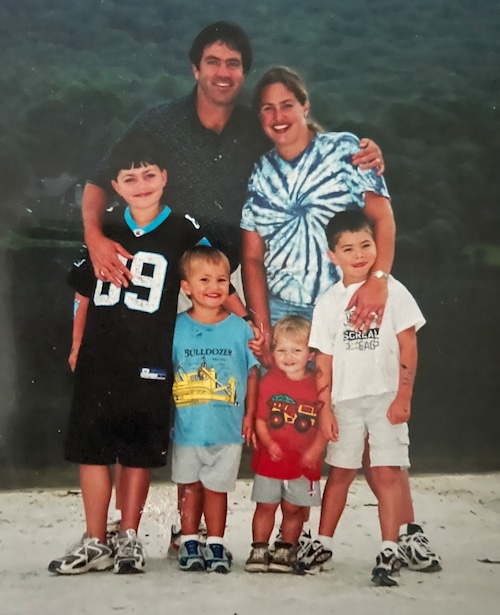

Growing up with four boys, the Maye house was always a lively place to be. Left to right: Cole, Drake, Luke and Beau. (Courtesy photo: Aimee Maye)Aimee Maye

That swagger, even at 9, came from expecting to win. Growing up in the Maye household, competition was always king.

“We emphasized winning,” Mark said. “We’d talk about, ‘Second is the first loser, man. It’s about winning.’ There’s such a difference. As the kids have gone along with their sports, the one-point losses, hey, the feeling with a one-point loss (compared to) a one-point win… sometimes you might not play good, but we emphasized win the game, then we’ll work on trying to fix (anything that’s wrong).”

A two-year starting quarterback at North Carolina, Mark was working as a graduate assistant when he met his future wife, then Aimee Sockwell, who had been a standout basketball player in her own right. Named Mecklenburg County Girls Player of the Year as a senior at West Charlotte High School, Aimee can be as competitive as the rest.

Mark knew he wanted a big family, and he and Aimee were blessed with four boys. Luke set the tone as a sports-crazed child, and Cole, Beau, and Drake all followed suit. For the Maye boys, winning was the only option, and that’s played out over the course of their athletic careers.

There are a pair of National Championships in the family, as Luke won a ring playing hoops at North Carolina, while Cole nabbed one pitching at Florida. Beau’s triumph over injury might be the most impressive feat of the bunch. With holes in his knee cartilage, he underwent nine surgeries and still walked on to the basketball team at UNC. And then there’s Drake, who has accomplished so much that the Patriots are entrusting him with the future of their franchise.

“We don’t like losing, as a family,” Cole said on his back porch in Charlotte. “That’s been one of our core values that our parents instilled in us.”

Fanatics Sportsbook

10X$100 BONUS BET

BET MATCH BONUS

Must be 21+. GAMBLING PROBLEM? Call 1-800-GAMBLER (CO, KY ,MD, OH, PA, TN, VA, VT, WV); (888) 789-7777 or ccpg.org (CT); 1-800-BETS-OFF (IA); (800) 327-5050 or gamblinghelpline.org (MA), mdgamblinghelp.org (MD), 1800gambler.net (WV)

Drake wasn’t just the youngest, but always the smallest growing up. Even at 6-foot-4, he still is. Luke and Cole were years older, and Beau, who only had Drake beat by 14 months, was a massive child.

“In elementary school, Beau was like ‘Elf,’” Mark laughs. “He was like the same height as his kindergarten teacher.”

Growing up, the boys competed at anything. Anything. Football. Ping pong. Pickleball. Putt Putt Golf. Regular Golf. Corn hole. Cards. Board games. Video games. And especially basketball, with games that were laden with physicality. Beau had a pair of broken elbows from going down hard on the concrete of the Mayes’ home court to prove it.

“That’s part of growing up with four boys and three brothers, man. It’s a war sometimes,” Beau said.

On the court, Drake was always a scrapper. He’d foul — often, his siblings say — because he knew he could get away with it. Contentious games would lead to brothers going full days without speaking to each other. Even in simple driveway games, the stakes were always high.

When Drake and Beau were 10 and 11, their parents sent them to a basketball camp with a 3-on-3 tournament at nearby Davidson. The two of them teamed up with a third friend, Bobby Waite. Every group of three had to fundraise, and the team with the most money got to select their “coach” from the basketball team.

At the time, Davidson had a decent little shooter named Stephen Curry.

The Mayes raised the most money, were awarded the No. 1 overall pick, and their coaching choice was a no-brainer.

“Obviously we’re going to pick Steph Curry,” Beau said.

Per usual, Drake was the youngest player, and reluctantly, Beau admits he was still the best player on the floor. Beau describes his younger brother as “a whirling dervish” and “a Tasmanian Devil” in those games. With Curry behind their bench, the Maye boys won the entire tournament.

“I bet Steph probably wouldn’t remember that,” Beau said. “But we do.”

Growing up, Drake was always the smallest of the Mayes.

Top row: Mark, Aimee. Front row: Luke, Beau, Drake, and Cole. (Courtesy photo: Aimee Maye)Aimee Maye

Even the virtual competitions between the Maye boys got animated.

They loved video games then and still do now, which helps with Drake heading to New England and Luke currently playing professional basketball in Japan. Whether it was NBA 2K, Mario Kart, FIFA, or anything else, the boys kept track of their rankings growing up. Everybody in the house knew who the belt holder was and who the next challenger would be.

“It didn’t need to be written down,” Cole said. “They’d be begging for the guy who held the crown to play another game.”

When the world stopped during COVID-19, the Maye competitions didn’t. The boys began playing Madden on franchise mode and Drake had a knack for winning the eight-team league no matter where he drafted. Cole estimated his youngest brother “probably won 12 of the 14 seasons.”

COVID-19 also introduced the boys to Pickleball. Two-on-two matches became commonplace, with raw power outweighing finesse.

“Everyone’s at the net and everyone’s spiking it and spiking it at each other,” Cole said. “We’re not holding back. At times, you wouldn’t even care if you get the point or not but you’re going to hit the ball as hard as you can at the guy across from you. Which, I don’t know if it’s the strongest strategy, but it’s more of a statement made.”

Pickleball is now a favorite of the Mayes, and Drake in particular is dialed in — both as a player and a trash talker. He’s recently taken to trying to beat people one vs. two, and according to Beau, has dubbed himself Roger Federer, Carlos Alcaraz and most recently, “right-handed Ben Shelton” in mid-competition.

“He loves talking (expletive). He’s the No. 1 (expletive) talker,” Beau said. “He knows it gets obnoxious and he continues to do it. Man, it fires me up! I’m sitting here talking about it and it’s making me mad.”

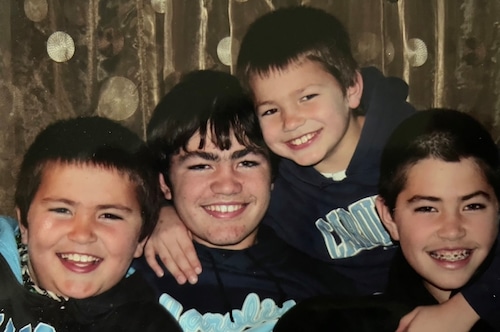

Drake Maye and his brothers were always North Carolina fans. Left to right: Beau, Luke, Drake, and Cole. (Courtesy photo: Aimee Maye)Aimee Maye

Drake’s rise to stardom really began to take off at Myers Park High School, where he transferred as a sophomore.

Gus Purcell Stadium sits atop a slight grassy hill, and at the base is a parking lot where fans can purchase first-class tailgating spots. Sold by the booster club, fans buy season passes and arrive early on Friday night with their flags flying.

When Scott Chadwick took over as football coach in 2014, the boosters were having trouble selling out the passes. They were still advertising at home games throughout the season, and there was a bunch of inventory left at the year’s end.

Fast forward to Drake’s junior year in 2019, where the program was on the rise and interest began to crescendo. The booster club announced the spots would be going on sale at 8 a.m. on June 1st. By 8:17 a.m., the entire parking lot was sold out. It took just 17 minutes.

“There were people that were afraid that they were not going to get in online that showed up at the booster club treasurer’s front door at 8 a.m. that morning because they wanted to make sure they got theirs,” Chadwick said.

Those tailgaters got more than their money’s worth.

During Drake’s final season — his senior fall was cancelled due to COVID-19 — he led Myers Park to a conference championship and was named North Carolina’s Player of the Year. The big-armed quarterback threw 50 touchdowns to two interceptions, while setting a Myers Park record with 3,512 passing yards; Drake put up video game numbers to rival one of his Madden franchise winners.

In addition to starring at football, Drake continued to turn heads on the basketball court. He likely could have been a terrific three-sport athlete given his prowess at baseball — he was a strong shortstop and center fielder growing up — but the game was a little too slow for him unless he was pitching.

In the locker room for the basketball team, there was a video game console with an outdated version of NBA 2K. The team would play it constantly — before practice, after practice, whenever — and Drake never lost. He made sure his competitors knew that too.

The kids kept standings on the whiteboard, and according to coach Scott Taylor, the top of the board read DRAKE MAYE in giant letters followed by his undefeated mark. With each win, Drake would update it as boldly as he could.

And though supremely confident in his own abilities, on the court, there was no selfishness. If anything, Drake was too passive early on. Because football season would bleed into basketball season, Drake wouldn’t arrive until the Mustangs were four or five games into the schedule, and at that point, he wouldn’t want to upset the chemistry his teammates built. Eventually, that wore off, and the team was better for it.

“He knew when it was time to put his foot in the ground and go ahead and stake claim,” Taylor said. “There were plenty of times where he would give you a look or look up from the huddle and nod and you knew that he recognized that it was time for his effort and impact to be felt.”

When Drake was with his teammates, it wasn’t how am I going to win? It was how are we going to win? Taylor used to try to stack the deck against him in practice scrimmages, and no matter who played alongside Drake, he found a way to elevate his team to victory.

“He’s a connector,” Taylor said. “He finds a way just to be able to make connections with everyone in (the locker room). It’s really easy for him and genuine. I don’t know if it’s just because of where he’s grown up, or what he’s grown up around, or just who he is. But he brings people together.”

Drake’s two high school coaches at Myers Park have strikingly similar stories about the only time they ever saw him dismayed: It was when he felt that he let his upperclassmen down.

In his sophomore year playing football, Drake threw three interceptions in the first half of a game against Butler. It was their lone loss of the regular season and ultimately cost Myers Park a conference championship. In the state 4AA playoffs, they’d see Butler once again.

“That whole week and that night, he told the seniors, ‘My bad last time we were here,’” Chadwick said. “‘It ain’t happening this week… You’re not going to finish (with a loss) this week. What happened last time ain’t happening here this week. I’ve got you this week.’”

A man of his word, Drake threw three touchdown passes and wasn’t picked off en route to a 33-8 blowout in the revenge game. Myers Park’s seniors didn’t go out with a second loss to Butler.

On the basketball court as a sophomore, Drake really arrived in a playoff game against Northwest Guilford. The football star scored 25 points, hit a 3-point dagger to essentially end things, and then literally ended the game with a steal and a dunk as time expired. He hung on the rim as the crowd erupted.

But that’s not what resonated with Taylor. Two games later in the tournament, Drake scored 19 points against R.J. Reynolds, but fouled out in a loss that ended their season. Though he was only a sophomore, Drake was distraught.

“He just kept saying, ‘Coach, I let my seniors down. My seniors are done,’” Taylor said. “He has another year to come back. He’s got another big football season ahead of him. He has so much more ahead of him, and he was stuck in the fact that his buddies, his teammates, his seniors, their career had ended right there. I know he’s never lost that.”

Whether it’s growing up with three brothers or simply how he’s wired, Drake has shown a fierce loyalty to those around him. He’s had the same girlfriend since the seventh grade — Ann Michael Hudson — and brought her on stage at his introductory photo shoot at Gillette Stadium, along with his brothers. Drake has also driven the same truck since he got his license, a white GMC Sierra, because he believed a quarterback should drive a pickup truck, Mark said. Though his rookie deal will pay him more than $35 million, he’s still rolling with his ride.

At Myers Park, there was one chant from opposing student sections that would really get under Drake’s skin on the basketball court.

“Luke is bet-ter!”

By the time Drake was in high school, Luke was a star at North Carolina. He’d hit a buzzer-beater to send the Tar Heels to the Final Four and had his National Championship ring. Drake wasn’t the only Maye that heard that chant — Beau shrugged it off — but he was the most motivated by it. Incredibly confident, Drake didn’t want to just be Luke Maye’s brother. He wanted to be Drake Maye.

“Drake’s not really someone you want to piss off when he’s in a competitive mood and he’s out on the (court) trying to win,” Cole said.

According to Taylor, Drake was even more driven than usual when barbs from the student sections started flying. He had a go-to shot — a mid-range fadeaway on the baseline — that he loved to drill in front of them. Then he’d turn to quiet the students down as he headed back up court.

“Growing up, especially going to Carolina, he was my brother, and he was my dad’s son,” Luke said. “He just kinda wanted to make his own name. I said, ‘The only way you can make your own name is by performing.’ He really did that. He really stepped up and had an incredible career.

“Now I’m more of Drake’s brother. I think it’s pretty cool.”

The Maye Brothers attend a UNC basketball game Left to right: Luke, Beau, Drake, and Cole. (Courtesy photo Aimee Maye)Aimee Maye

When Drake arrived at Chapel Hill, his coaches were greeted by more of the same. A self-assured kid who was hellbent on being the best. Tar Heels coach Mack Brown has the broken ping pong paddles from losses to prove it.

At 68 years old, Clyde Christensen has enjoyed a front row seat to some of the best quarterback play football has to offer. A quarterbacks coach for Peyton Manning in Indianapolis and Tom Brady in Tampa Bay, Christensen served as an offensive analyst on Brown’s staff while Drake was at North Carolina.

The first thing that jumped out to Christensen?

On the golf course, Drake wouldn’t tell his brother Beau that a ball 4-and-a-half inches from the pin was good.

“We have a strict no gimme policy,” Beau explained. “Every putt has to be putted out. Over the years we’ve had some very, very, very, VERY short putts be missed, so we always putt everything out. And we want an accurate score too. Whether you shoot 83 or 103, that number should be the actual number of strokes.”

So Drake made Beau putt it out, and Christensen learned that day that nothing is given when competing with the Maye family.

“(Drake) just has a playfulness. Tom (Brady) had the same thing, a playfulness where they love to compete,” Christensen said. “They love to win $5 off you. They love to win a $2 bet. Nobody loves winning a $2 bet better than Tom Brady. This guy has the same kind of fun, ‘Hey, I’ll bet you that you can’t hit the crossbar from here, Clyde.’ Always, everything turns into a competition.”

On the field, Drake’s dedication to teammates stood out in addition to outstanding play.

His sophomore year is what rocketed him up draft boards — Drake threw for 4,321 yards and had 38 touchdowns to seven interceptions — but late in his junior year, his character was once again revealed. There were plenty of personnel changes on offense, from the coaching staff to the supporting cast, and it turned into a turbulent season.

Drake was still clearly going to be a Top 5 pick in the NFL Draft, and in the season finale against N.C. State, North Carolina was getting thumped, down 26-7 at halftime. The game didn’t matter in the standings; the Tar Heels had no way to win their way into the ACC Championship game.

”It would have been really easy for him to just ride off into the sunset knowing where he is in the draft, and the guy just kept competing,” offensive coordinator Chip Lindsey said. “I go see him at halftime, we’re down, and he’s like, ‘Coach I like this (play), I like this (play), I like this (play), let’s go back to this.’ There was never any inkling that he wasn’t going to compete all the way until the end.”

There was no dramatic comeback. North Carolina fell to their rivals 39-20, but the quarterback’s willingness to continue answering the bell left a lasting impression. For Drake, there’s no such thing as a meaningless game.

“In fact, he tweaked his ankle a little bit and went back into the game,” Lindsey added. “I thought he was going to be out. (Other staffers) were telling me he was probably out. Then we get the ball back and he runs on the field. Those are the kind of things that really stick out to me. Just about his drive and how important it is for him to be there for his teammates.”

Foxborough, MA – April 26: New England Patriots QB Drake Maye at his introductory press conference at Gillette Stadium. (Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)Boston Globe via Getty Images

With the name Drake Maye forged in North Carolina lore, there’s a new challenge now as he heads to New England.

In 2023, the Patriots offense wasn’t just bad. It was lowest scoring offense of any team in the NFL over the past decade. Sooner or later, New England will turn its hopes to the No. 3 overall pick to right the ship. Once again, Drake will be battling opponents more experienced than him, but he’s been doing that since he started toddling in Huntersville.

New coach Jerod Mayo has already gotten a glimpse of his competitive side — the two squared off in the NHL video game during Drake’s Top 30 visit — but there’s plenty more that he will learn.

The linchpin in New England’s rebuild, turning an NFL franchise around will be the most arduous task Drake has ever faced. But this is the kid who called his shot with Nick Saban. Who won a 3-on-3 tournament with Steph Curry. Who outshined his National Champion brother at North Carolina. Who sold out the whole darn tailgate in 17 minutes.

If there’s anyone with the confidence to turn things around in Foxborough, it’s Drake Maye, who has never lost the fire of being the little brother.

“It’s funny that the really great players that I’ve been around just came from great families,” Christensen mused. “Which, it may be random, it may not be. I don’t know. But everyone from the Hasselbecks to the Bradys to the Mannings to the Lucks, they just were special families — and this kid has the same thing.”