First of two stories.

CHICOPEE — A hit-and-run driver last November killed Gayle Gould’s only living sibling, her brother Gary.

Gary Turcotte, 62, died after being struck in a crosswalk near his apartment on Chicopee Street. “My brother was outgoing. He wanted to help people,” his sister said.

“Everyone knew Gary,” said Susan Santoro, Turcotte’s neighbor. “He was a fixture in the neighborhood. It was very sad.” A Springfield man was arrested and faces charges, including motor vehicular homicide.

Just two days before Turcotte’s died, another man, William Matteson, was struck and killed while walking just blocks away on Chicopee Street. The driver, who pleaded not guilty to motor vehicular homicide while intoxicated, told police he was going 35 or 40 mph in a 25 mph zone.

Turcotte and Matteson were among the five pedestrians in Chicopee killed by cars in 2022, the third-highest number that year of any city or town in the state, after Boston and Worcester, according to an analysis by WalkMassachusetts.

About a week after Turcotte’s death, a bicyclist was hit and killed on nearby Meadow Street. Then, early this year, Ruben Colón was killed in a crosswalk at the southern end of Chicopee Street.

Visual reminders of these tragedies remain: A bundle of faux flowers and a stuffed animal memorialize Colón near where he died. Matteson’s obituary is taped to the checkout counter in Jenrose Wine & Liquors, where he worked.

Gary Turcotte smiles on his 58th birthday. Several years later in 2022, he was struck and killed by a car in Chicopee. (Photo courtesy of Gayle Gould).

Across the country, there’s more people like them to mourn.

Pedestrian deaths have been on the rise nationwide. Last year, an estimated 7,500 people died, the highest number since 1981, according to an analysis by the Governors Highway Safety Association. In Massachusetts, a record 101 pedestrians were killed last year.

It’s not just Chicopee that’s faced the issue in Hampden County. In 2021, Springfield tied with Boston for the most pedestrian deaths in the state, with the death toll in both cities at nine people, according to an analysis of state date by WalkMassachusetts.

Fatalities in Chicopee have rattled neighborhoods like Willimansett, where several pedestrians were killed. Officials and city councilors are discussing street safety, police have worked on enforcement and even done sting operations in crosswalks.

And the Department of Public Works rolled out a project to make areas like Chicopee Street safer for pedestrians. Some are pushing for more changes, while others mourn the family they lost.

Cellphone distractions

Climbing pedestrian fatalities across the country worry experts like Michael A. Knodler, director of the University of Massachusetts Transportation Center and a professor of civil and environmental engineering.

In pedestrian safety, vehicle speed is key. When a car is going 20 miles per hour and hits a person, there is a 18% chance of serious injury or death, Knodler said. When the car is traveling 40 miles per hour, the chance increases to 77%. “Just slight changes in speed really change the dynamics of the crash,” he said.

Distracted driving with cellphones is a huge problem too, Knodler said. Slowing traffic is one strategy to help reduce injury. “At the very least if they’re going to be distracted,” he said, “we know they will be going slower.”

UMass was chosen to lead the newly created New England University Transportation Center with a $15 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation. Eight colleges and universities are involved, including Holyoke Community College. Knodler expects one of the first projects will be in the Springfield, Holyoke and Chicopee area.

The Republican did its own speed testing in Chicopee using a radar gun from the UMass Transportation Center in several locations with fatalities.

On the south end of Chicopee Street, 7% of vehicles driving north in a 30-minute period were going 10 mph over the limit. Northbound on Meadow Street, about 2% were speeding by 10 mph or more. On the 400 block of Springfield Street, 7.5% of southbound cars were going 40 mph or higher in a 30 mph zone.

Two pedestrians were struck and killed on that block last October. No charges were filed in one case; in the other, charges were filed against the driver, who was allegedly driving at least twice the speed limit.

On the 800 block of Chicopee Street, the Department of Public Works collected how fast each car was going for a week in June. Tubes on the street collected the information 24 hours per day, according to Christopher J. Chaban, the assistant city engineer.

Crossing light installed on Chicopee Street where Ruben Colón, 78, was struck and killed near the intersection of Florence Street in February 2023. (Hoang ‘Leon’ Nguyen / The Republican)

More than 100,000 cars went by with an average speed of about 29 mph and a median speed of about 30 mph. Just 0.1% of cars were going more than 50 mph. The speed limit there? A sign posted shows 25 mph, but signs will likely state a higher speed limit soon.

Incorrect 25 mph signs were put in more than 20 years ago during a road reconstruction project on the north end of Chicopee Street, Doug Ellis, the city’s engineer, told a Department of Public Works meeting in mid-September. On the street’s north end before the Willimansett bridge, the limits are 30 and 35 mph, depending on the location, according to a special speed agreement with the state, Ellis said.

In that meeting, city councilors questioned speed limit signs on the street. Elizabette Batista, superintendent of the Department of Public Works, said the 25 mph signs should be removed and corrected.

‘Speed happens everywhere’

Police say speed is a factor in the spate of crashes.

“We can’t say it’s not a factor,” said Travis Odiorne, the police department’s public information officer. “Speed happens everywhere.”

The department has used grant funding to send officers out to patrol for speeding. “Obviously they can stop cars for violations,” Odiorne said, “but with our call volume so high, we’re running from call to call to call.”

Police have looked at other infractions, too. Last spring, police used a grant to conduct sting operations in crosswalks. Officers in plainclothes who drove to the area in unmarked cars would step into a crosswalk and see if a driver would stop. About 125 citations and warnings were given out in four weeks, Odiorne estimated.

To try to enforce the speed, a city employee also drove the speed limit up and down Chicopee and Meadow streets for 19 hours a week from April through June. It was a “pace car,” as city officials called it.

The pace car isn’t on the street slowing traffic any longer. “Our intentions are to start that project again,” Mayor John Vieau told The Republican, adding that the city was working on renewing a contract for the initiative.

Vieau himself lives on Chicopee Street. “Frankly, a guy that walked in front of my house every single day was hit,” he said, referring to Colón. “I was losing sleep over it.”

Vieau pointed to positive changes since Colón’s death — like a DPW road improvement project and police ramping up traffic enforcement.

People crossing the street need to pay attention, he said, and drivers need to slow down and put their phones down. In the last year, someone was cited for driving in the city while watching a movie, he said. “That’s just not OK.”

‘A safer place to live’

Marisol Nazario has lived on Chicopee Street for several years. She can rattle off a list of fatal accidents in her neighborhood. “People drive recklessly,” she said. Her fiancé takes the family’s car to work, so she often walks the neighborhood and accompanies her middle school-aged kids to their destinations to make sure they arrive safely.

Her family has had close calls. About two years ago when her daughter, then 11, was getting off the school bus, a car didn’t stop for the bus’ stop sign and she was nearly hit, Nazario said. There’s also the time she and her kids walked to the nearby gas station right after moving into their Chicopee Street home, and they nearly got hit in a crosswalk. “It’s happened so many times, I’ve gotten used to it,” she said.

Christine Weichel lost her husband, Nickolas Weichel, last fall when he was crossing Springfield Street and a car that police said was going at least twice the 30 mph speed limit hit him. Surveillance footage showed he seemed to see the car coming at him and tried to shuffle to avoid being hit, a police report says.

When Nickolas died, the Chicopee couple was about a month shy of their one-year wedding anniversary.

Christine Weichel and Nick Weichel on their wedding day in November 2021. Last year, Nick was hit by a car in Chicopee and died. (Image courtesy of Christine Weichel)Submitted photo

“He was my other half,” Christine Weichel said. “Since he’s been gone it’s been really hard. I can feel that part of me missing.” She recently organized a golf tournament in his memory.

Since her husband’s death, Christine Weichel has been thinking about how speed bumps could help that area of Springfield Street. “There’s always pedestrians on that road,” she said.

The driver, Nazier Grandison, has been charged with manslaughter and motor vehicular homicide. A jury trial in Hampden Superior Court is scheduled for early 2024.

“I just want it to be over with at this point,” Weichel said of the court proceedings. It’s hard for her to know Grandison is out on bail when her husband is dead, she said.

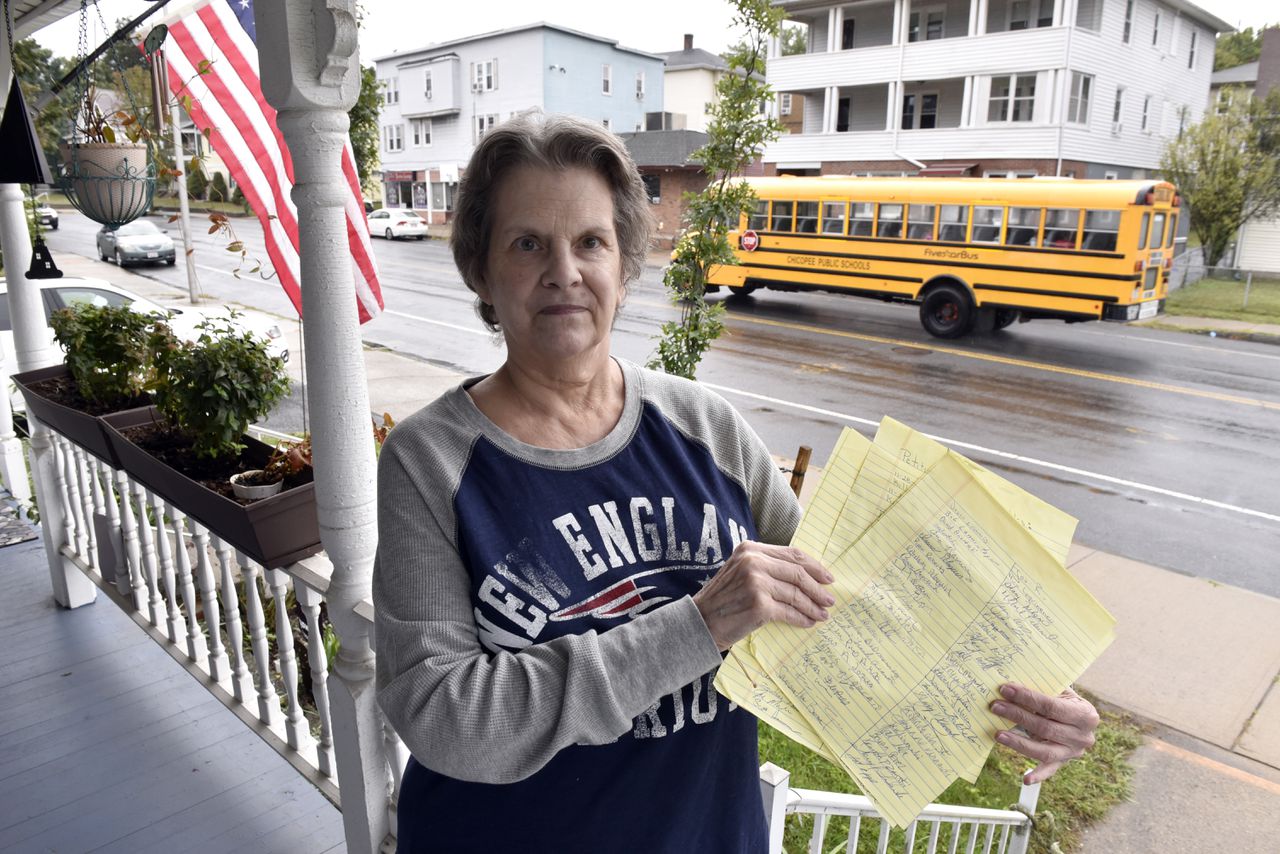

Susan Santoro holds a petition she started to get the city of Chicopee to improve road safety in the wake of numerous pedestrian accidents. She is on her Chicopee Street porch, just up the street from where her friend was killed by a motor vehicle. (Don Treeger / The Republican) 9/18/2023

After Susan Santoro of Chicopee Street lost two people she knew in just a few days ― Turcotte and Matteson, she took action.

On a yellow legal pad, she started a handwritten petition for “speed tables,” longer and flat-topped speed bumps. “I want a safer place to live,” Santoro said, sitting in her living room as traffic outside hummed. “I know we’re going to have traffic, but it can’t be a raceway.”

Last fall, she put the petition down the street at Jenrose Wine & Liquors for neighbors to sign, and more than 200 people did. People came into the liquor store not to purchase beverages, but just to sign the petition, said Manager Al Patridge.

Though there aren’t speed tables on Chicopee Street, there are revamped crosswalks and lights.

After the spike in pedestrian deaths last year, the DPW looked at how it could make the streets safer.

“Even one death would have sparked it, but it was so many,” Batista said. “What can we do to maybe help reduce this? Because we can’t eliminate it altogether — we can’t fix distracted driving, it’s really difficult.”

Impaired driving, too, is a nationwide problem, she said. “What we do try to do is maybe make things a little bit more visible,” Batista said.

A typical road is 30 feet wide, but parts of Chicopee Street are 50 feet wide. In some spots on the street, medians are being installed in the middle of crosswalks to narrow the lane and give pedestrians a place to pause if needed. Flashing beacons light up the crossing.

There’s a new median and lights in the crosswalk near Jenrose Wine & Liquors where Turcotte was killed, and near where Colón was killed on the south end of Chicopee Street, a crosswalk now has flashing lights.

Chicopee city councilor Delmarina López pays respect at the memorial for Ruben Colón, 78, who was struck and killed on Chicopee Street near the intersection of Florence Street in February 2023. (Hoang ‘Leon’ Nguyen / The Republican)

It wasn’t possible to make the changes right away though, Batista said, in part because the wave of deaths happened in late fall and winter and the ground was frozen. Prior to the spate of pedestrian deaths, she said she had not received complaints about the area.

“One thing I think people need to understand: it takes patience,” Vieau said. Engineering work has to be done, and the city needs see how changes may affect plowing and drainage.

City councilors who represent Chicopee Street are frustrated by the city’s response time. “When it all first started I think we didn’t react fast enough,” said Ward 7 Councilor Bill Courchesne. “But unfortunately everything takes time.”

He wants to see speed tables on parts of Chicopee Street. A request he made to add signs reminding drivers to yield in crosswalks was just approved by the Department of Public Works. For now, they won’t be ones with light-up beacons, as Courchesne wanted. The city will try putting up non-lighted signs it has before purchasing any others, Batista said at the mid-September public works meeting.

Courchesne lives near Chicopee Street. He hears people speeding. Recently he almost hit a biker who cut in front of his car in the dark without a bike light. “Luckily, I saw him,” he said. Both drivers, walkers and bikers need to be careful, he said.

“There’s two victims at the end of the day — obviously the person hit and losing their life and the person who has to live with that.”

Early this year, Ward 3 Councilor Delmarina López asked in a council order that the DPW look at putting lights on a number of crosswalks, including one on Chicopee Street in the crosswalk where Colón was struck and killed about 10 days later.

“We shouldn’t wait until something happens to take action,” she said, standing near a memorial to Colón on Chicopee Street. “This could have been done years ago.”

Crossing light installed on Chicopee Street where Ruben Colón, 78, was struck and killed near the intersection of Florence Street in February 2023. (Hoang ‘Leon’ Nguyen / The Republican)

On a recent morning, López pressed a button for the crosswalk light. “Yellow lights are flashing,” the crosswalk announced in its robotic voice. After several cars rushed by, traffic in both directions braked. “None of those cars would stop without the lights,” she said while walking across the street.

The median and lights on the crosswalk outside of Jenrose Wine & Liquors are new, so it’s early to see what their impact may be, Patridge from said behind the shop’s counter, where Matteson’s obituary is taped. It seems to him that more drivers have been stopping for pedestrians.

Still, what they need he said, “is people paying attention.”

COMING MONDAY: More than 20 pedestrians have died on Springfield streets since 2020. What’s being done to make streets safer?

Reporter Jonah Snowden contributed to this report.