Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. This story is part of the series “Migrating and Vanishing.”

The sister of Aurelio Cruz López holds a sign used in the search for the young man, who disappeared along the U.S.-Mexico border.Photo by Andrea Godínez

I am Araceli Cruz López, an indigenous Tzotzil woman. My little brother was born on June 8, 2003. He was one month shy of his 19th birthday when he disappeared while attempting to migrate to the United States. I live in a camp of displaced people in Chiapas, Mexico. Where do I go? Who do I turn to? Where do I start?

The question repeats itself. The answers do not. At an institutional level, there are multiple failures when it comes to the search for missing migrants. There is a serious forensic crisis in Mexico: 56,000 unidentified bodies and more than 100,000 missing persons. A law regarding the search for missing persons has been in place since 2017, but most of its requirements are not complied with. Identification mechanisms are disjointed and depend on the will of each state.

The team of Voces Mesoamericanas supports families of missing migrants in their search.Photo by Andrea Godínez

The data kept by the National Search Commission (CNB, per its Spanish acronym), the agency in charge of searching for people in Mexico, is deficient and contradicts the numbers provided by the state prosecutors’ offices. In the context of a national crisis, who is searching for the migrants?

Civil society organizations, such as the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF, per its acronym in Spanish), the Foundation for Justice and the Democratic Rule of Law (FJEDD) and Mesoamerican Voices, Action for Migrants, among others, have made progress with the families in this regard by establishing networks among themselves, while trying to do the same with some states.

Aurelio was found by trackers

On May 4, 2022 at 3:30 a.m., 18-year-old Aurelio Cruz López called his sister Araceli. He had departed from the town of San Cristóbal de las Casas in the state of Chiapas on April 28, from a camp for people displaced by violence. At first he wanted to look for work in the state of Sonora, but he encountered two young men who insisted that he was better off crossing the border into the U.S., where he would have more opportunities to help his family.

Aurelio joined the two men until they ran into U.S. immigration officials and dispersed. It was at that point that Aurelio lost his backpack. At 8:40 a.m. he sent an audio message to his sister:

We no longer have water. I lost my backpack the moment I ran away. I lost my food. My companion has some water left but it’s not much. We will keep walking until we reach our destination. Don’t worry mom will be taken care of there.

“My little brother left because he needed a job, a better life, to get ahead. We don’t have a decent house where we can stay. We are in a temporary camp with my family. Our father was killed because of the armed conflicts in the communities,” says Araceli Cruz López.

The companions her brother was traveling with told her that he had passed out in the desert when they were already in the U.S., in the vicinity of the Tohono O’odham reservations. “We asked his companions to call immigration and tell them where he was, to send them the coordinates so they could rescue him alive. But unfortunately they did nothing. Maybe they were afraid,” says Araceli, sitting on a log outside a makeshift house, crying.

Tents that house displaced families in the municipality of Chenalhó, Chiapas.Photo by Andrea Godínez

Araceli’s entire family was displaced by armed conflicts in the municipality of Chenalhó in Chiapas. As a result of these struggles, she has contact with social organizations. When she learned that her little brother had been left in the desert, she called an acquaintance in California and asked for help. That person sent her the phone numbers of groups of people in the U.S. who search for migrants who have disappeared in the desert. Araceli gave the trackers the coordinates she had and called the Mexican consulate in the U.S.

Three groups of trackers joined forces to locate Aurelio, and 23 days later they found the remains of a body. It had one sneaker on, but there was not much else. There was no fanny pack with his documents, no other clothes and no backpack. Araceli could not accept that this was her brother.

Aurelio was identified by civil society organizations

“At the moment we could not accept that information because we did not know if it was really him. So we filed a missing person report with the prosecutor’s office here. But they never gave us support: neither the government, the prosecutor’s office, nor the Search Commission. They didn’t conduct a proper search,” Araceli says.

She then insisted that the Mexican consulate in the U.S. conduct a DNA test. At that point, the family began to work with the lawyers at Mesoamerican Voices and the EAAF.

“We wanted to know if the body was really my brother. The Argentine groups did the DNA test for us. It was a five-month process. They didn’t leave us alone with our sadness, and for that we thank them,” says Araceli.

Araceli cries while talking about her brother who disappeared along the border and whose remains were repatriated.Photo by Andrea Godínez

Sandybell Reyes oversees the migrant advocacy program at Mesoamerican Voices, Action for Migrants. She was among those who supported Araceli during the identification process: “It is very sad and frustrating for the families when they initiate these procedures, file complaints with prosecutors and search commissions, and find that the only response is another question: ‘What else do you know?’ When what they should be doing is requesting information from their counterparts.”

The first thing Mesoamerican Voices does when a family gets in touch is provide information so that the relatives can decide how to proceed: by filing a report with government institutions, undertaking a search among civil organizations, or performing an informal search (alongside government institutions) to determine if the person is in jail or hospitalized.

Most of the time, Reyes explains, the families opt to start with an informal search, because there is still hope that the missing person will return, and then proceed with prosecutors’ offices, search commissions and victims’ commissions.

Araceli had to wait seven months to confirm the worst news. “It turned out to be my little brother. They found him at the coordinates I had provided. He was incomplete: he no longer had his two arms and they could not find them. We finally accepted it because of the DNA testing process.”

How was the institutional process of the search?

The first thing Araceli did was visit the local prosecutor’s office to make a statement, to report that her brother was missing. Then she contacted the lawyers from Mesoamerican Voices, and returned to the prosecutor’s office with them to ask questions. They told her that she had to go to Altar, a municipality in the state of Sonora, where the investigation was going to take place.

But that wasn’t an option. She didn’t have the money to travel and to insist at another prosecutor’s office that the search go forward.

“It is very frustrating when they are told that since the last communication was in a border state, their investigation is going to be conducted in that place. It may sound logical, because that is where the disappearance took place and that is where they have to look, but if we are talking in terms of access to justice, the family member is not going to go there to ask for information. And with a system that does not work if you are not there at all times to follow up, it turns out that the families do not have any information about their missing relative,” says Reyes, confirming what all the cases interviewed for this investigation show. “So it doesn’t matter if they denounce or not, because in the end the search is a collective effort of the families of missing persons.”

Araceli took the institutional route, filed a report, found lawyers. But the national authorities responsible for searching , she says, were of little help: “Neither the prosecutor’s office nor the Search Commission did anything. It is really very sad. When you don’t have lawyers, they don’t take you into account. They discriminate against us for being indigenous and for being Tzotzil speakers.”

Araceli and Aurelio’s mother could not file a complaint because she does not speak Spanish. To alleviate these problems, once again, family members and organizations such as the Grupo Motor de Trabajo Psicosocial en Migraciones (Psychosocial Working Group on Migration), formed by civil organizations from Mexico and Central America, among them Mesoamerican Voices and ECAP, the Psychosocial Action and Community Studies Group in Guatemala, work together to provide information to migrants.

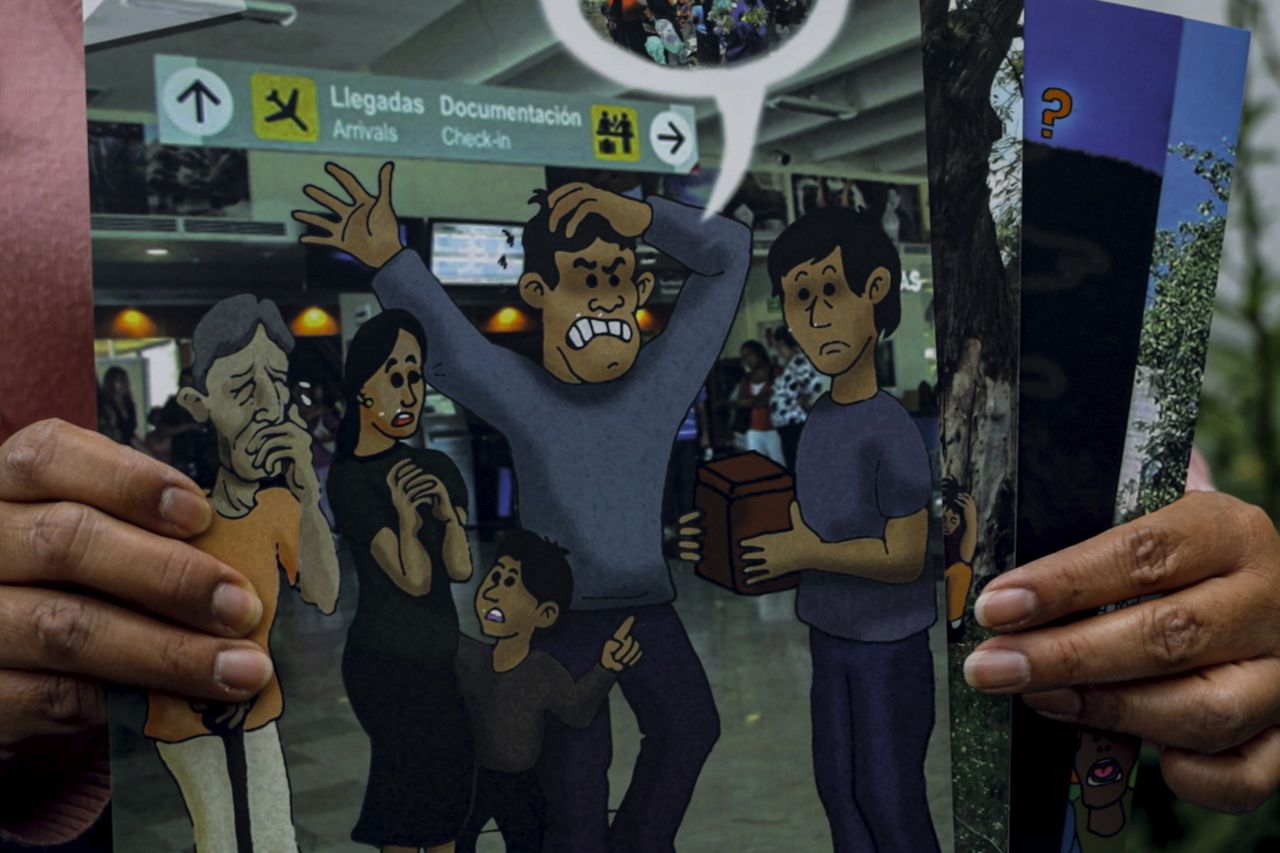

The group put together booklets with 20 illustrations explaining the search process for missing migrants: “Many of the people who are going through this search process do not know how to read or write, so the material is mainly graphic,” the booklets say.

Booklets created by civil society organizations to explain to illiterate people who searches for missing migrants are done.Photo by Andrea Godínez

Mexico’s uncertainty regarding missing migrants

State prosecutors in Mexico are expected to report the total number of missing persons in their states, including migrants, to the CNB. However, there is a discrepancy between the figures reported by the CNB in the National Registry of Missing or Unlocated Persons (RNPDNO, per its acronym in Spanish), and those reported by the state prosecutors’ offices.

As part of this investigation, 157 requests for access to information were sent to each of the prosecutors’ offices, the CNB, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the National Migration Institute of Mexico.

After pouring over the figures given by local prosecutors’ offices, we discovered that migrants reported missing in Mexico between 2017 and 2022 may be either 1,270, according to state prosecutors’ offices, or 124, as reported by the CNB. It is estimated, then, that less than 10% of the reports from state prosecutors’ offices on missing or unlocated migrants are accounted for in RNPDNO.

The only certainty is that Mexico does not know how many migrants have gone missing in its territory, nor how many of them have been found dead.

This investigation was produced with the support of the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR) led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).

__

Verónica Liso is an Argentinean product manager for digital native media and a freelance investigative journalist since 2013. She specializes in judicial journalism and data journalism. She has published in Cosecha Roja, Infojus Noticias, Página 12, Revista Anfibia, eldiario.ar, Perycia, among others.

Rosario Marina is a journalist specializing in data and narrative. She studied at the National University of La Plata, in Argentina. She has been covering human rights, gender and LGBTIQ issues, migration and police violence for 10 years for media outlets in Spain, Guatemala, the United States and Argentina.

Gabriela Olga Villegas is a regional digital content editor for Univision Texas and Chicago. She is the winner of a Lone Star EMMY for winter weather coverage in North Texas with the Noticias 23 team. She worked for more than seven years as a journalist for El Norte and Reforma in Monterrey, Mexico, where she began in daily news coverage and also conducted investigative journalism focused on corruption that had a national impact, such as the detour of resources in social programs and the favoritism of politicians with companies to distribute contracts and bids.

Andrea Godínez is a Guatemalan social communicator with a career of seven years dedicated to photojournalism and production of journalistic content, covering issues of migration, poverty and social inequality. She studied Communication Sciences at Universidad Rafael Landívar.