When Nashoba Valley Medical Center and Carney Hospital in Dorchester closed their doors for the final time last week, scores of workers suddenly found themselves without a job.

And with the hospital’s owners, Dallas-based Steward Health Care, in the middle of a messy federal bankruptcy case, many more employees at the chain’s other Bay State facilities are thinking about their futures.

Do they stay? Do they retire? Do they pursue another line of work?

That’s where Tim Foley and Ellen MacInnis come in.

Foley is the executive vice president of 1199 SEIU United Healthcare Workers East. The massive union represents health care workers statewide, including those at Steward-owned facilities in Massachusetts.

MacInnis is a nurse at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. She sits on the board of directors of the Massachusetts Nurses Association, which represents unionized nurses, including many who worked for Steward-owned facilities.

Since Dallas-based Steward filed for bankruptcy in May, the two union leaders have been helping workers navigate the crisis and, as necessary, help them find new jobs.

It hasn’t been easy. And it’s often been painful.

The workers “stood together through this very difficult time to do their job, to provide high-quality community health care services for the residents of Massachusetts and beyond,” Foley said during a news conference in Boston last week.

- Read More: They rallied to save Dorchester’s Carney Hospital. It might not be enough | John L. Micek

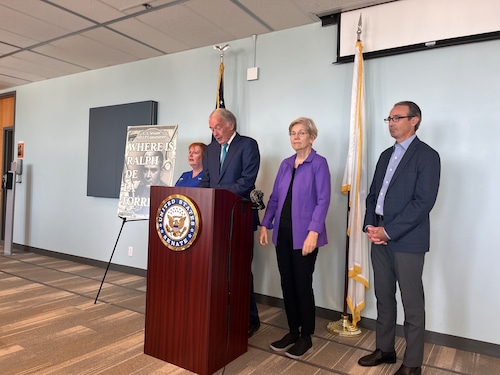

He and MacInnis were on hand to lend their voices to an effort led by Democratic U.S. Sens. Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren to hold Steward’s high-flying CEO, Ralph de la Torre, accountable for the company’s implosion — and his apparent defiance of a congressional subpoena.

Their indignation and frustration at that news conference was palpable.

U.S. Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., speaks during a news conference at the John F. Kennedy Federal Building in Boston, on Thursday, Sept. 5, 2024. Markey and other lawmakers spoke about the financial collapse of Steward Health Care (John L. Micek/MassLive).John L. Micek

Since Steward’s bankruptcy filing, labor leaders “have really stayed focused on three, main priorities,” Foley continued.

That’s “[continuing] to provide high-quality health care services at community hospitals; [fighting] to maintain operations, and to keep all [the] hospitals open during bankruptcy proceedings.”

That got a little harder after Nashoba Valley and Carney closed for good on Aug.31, Foley acknowledged. But it’s also good news that six other Steward hospitals in the state are on the way to being sold, he added.

MacInnis, who said she’s spent “decades” at St. Elizabeth’s, the company’s financial collapse has hit close to home.

While Steward boss de la Torre “sailed on his yachts, flew on his jets and vacationed around the world, those of us in the trenches of his depleted and embattled hospitals were forced to care for patients in understaffed units with broken and missing equipment,” MacInnis said, her Boston accent adding extra punch.

Nurses were also forced to contend with “missing supplies,” while “nurses brought in their own food,” to help feed patients living with diabetes, she added.

There’s also the very real work helping displaced employees from Carney and Nashoba find jobs and making sure that they’re paid the severance money that’s owed to them, the union leaders said.

“We’re doing everything in our powers to protect our members … their rights and what they have earned during their careers,” Foley said.

Last month, all 11 members of the Bay State’s Capitol Hill contingent sent de la Torre a letter, urging him, and another top executive, to honor those obligations.

So far, there hasn’t been an agreement, but Foley said he’s hopeful it’ll be ironed out soon.

“We’re trying to work on those issues so that people can make decisions around what they want to do with their lives and their career[s],” he said.

The Healey administration also has been lending a hand. Officials from the state’s Office of Labor and Workforce Development met with workers from both hospitals to help them find work.

Gov. Maura Healey similarly has called on Steward to honor its commitments to the workers, her office said in a statement last month.

“Steward must keep its commitments and make good on all severance payments to these workers as part of any Massachusetts sales,” Healey said. “We are insisting on worker severance in our negotiations and will insist on severance funding to the Bankruptcy Court if that’s what it takes.”

MacInnis has seen the impact on the nursing floor, with some nurses deciding that they’ve just had enough.

“There are a lot of openings. And Steward has been abysmal at filling openings. Some folks are just retiring. Carney had a lot of nurses,” she said. “They’re very committed to the hospital. And they’re just ready to be done.”

At this point, the trick is matching people not just with jobs but with positions that match complicated family schedules that have been in place for years.

“There are disruptions for people who have to pick up their kids at the end of the day, and the schedules that they have for many years,” Foley said. “So we’re trying to find the right fit for them.”

While they’re leaning into the work, it also was readily apparent from their comments last week that these two union leaders would rather not be doing it.

And for that, they blame Steward, and its mismanagement of its Massachusetts hospitals.

“I come today to share [my] disgust at this loathsome behavior, and to register our support for any and all efforts you can muster to hold this greedy coward accountable for the suffering he has caused and the damage he has done to our health care system here in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” MacInnis said.

And the work goes on.