This story was originally published by WBUR.

It started off like countless other Uber rides in downtown Boston.

A group of friends piled into a car after hanging out at a bar. Then, they started arguing. Most of the friends got out at their hotel, and the man offered to drive the remaining rider around to “collect herself.”

But when the woman asked the driver to drop her back off at the hotel, he refused.

Instead, he took her to his apartment in Dorchester that Saturday in July 2016 and sexually assaulted her, police alleged in court records.

A DNA test identified the suspect as Alvin Campbell Jr., a burly 43-year-old with a long criminal history and a prominent relative. Campbell is the brother of Andrea Campbell, then a Boston city councilor and now the state’s attorney general.

Despite the DNA evidence, Alvin Campbell was never arrested or charged in connection with the encounter. And police never alerted the public.

Over the next two years, a WBUR investigation found, three more women shared similar stories with police about a man who assaulted them after offering them rides at Boston bars.

In each case, DNA and other evidence pointed to Alvin Campbell, according to an application for a search warrant obtained by WBUR. And each time, authorities decided not to detain him or seek criminal charges.

Boston police finally arrested Campbell in early 2020 after a fifth woman reported she was raped. At that point, investigators made a horrifying discovery. They found evidence on his phone indicating he had sexually assaulted at least 10 additional women since the first incident in 2016.

Alvin Campbell is brought into Suffolk Superior Court in handcuffs for a 2023 hearing in his ongoing case. He’s accused of raping eight women and attempting to rape a ninth. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

Experts say the case is a striking example of how police and prosecutors often fail to take action when victims report sexual assaults, potentially allowing serial rapists to remain at large. A study sponsored by the research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice found that fewer than 1 in 5 rapes reported to police leads to an arrest. Even fewer result in convictions.

“This is a nationwide problem,” said University of Massachusetts Lowell criminologist Melissa Morabito, who co-authored the study. “The whole way that sexual assault is treated within the criminal justice system is in need of reform.”

Morabito and other experts point to a long list of potential reasons. Sometimes victims don’t want to testify because of concerns about the public court process or retaliation. Investigators sometimes fail to test rape kits or follow up on other leads. Law enforcement agencies don’t always share information. And the cases can be difficult to win in court, because it’s often the victims’ word against the accused.

In Massachusetts, the problems are compounded by a state privacy law that requires police to keep both arrests and incident reports secret in cases involving sexual assault. The controversial law makes it more difficult for the public to learn about serial rapists and examine how law enforcement agencies handle the cases.

Quincy, for instance, recorded six rape cases involving unknown assailants from 2019 to 2021, the department said in response to a public records request. But the city said it never alerted the public and declined to provide details or share the police reports, citing the privacy law that says sexual assault reports must be kept confidential.

Quincy Police Lt. Terence McDonnell said the department has no indication the six assaults were related or committed by the same person. He did not respond to questions about whether the city has received additional unsolved rape reports in the past two years.

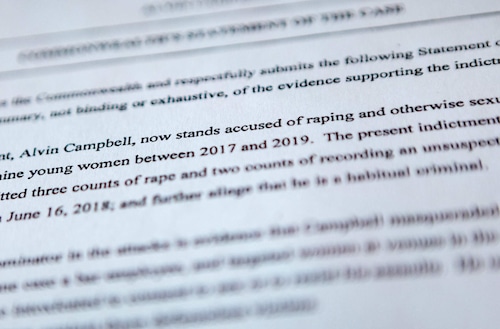

Prosecutors detailed allegations against Alvin Campbell in a 2021 Suffolk Superior Court filing. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

Boston and Medford police also cited the same law to withhold records about the sexual assaults involving Campbell from WBUR, making it harder to determine exactly why authorities failed to act sooner.

Even some information that is supposed to be publicly available is hard to find. For instance, some of the early assaults are only detailed in a successful request to obtain video and other records from Campbell’s phone after his arrest in 2020.

But clerks at the Boston Municipal Court’s central division said they were unable to locate the application for a search warrant, despite repeated requests by WBUR over several months. WBUR eventually obtained the document from the Suffolk County district attorney’s office.

The government’s case against Alvin Campbell

Campbell grew up in Roxbury and graduated from a vocational high school there. According to interviews and other public records, Campbell spent much of his adult life cycling in and out of state and federal prison for physical assaults and gun convictions.

He is now awaiting trial at the Nashua Street Jail for the rapes of eight women and attempted rape of another, making this one of the state’s largest cases of serial sexual violence in recent memory.

Campbell has pleaded not guilty, claiming the encounters were consensual. He has also been linked through DNA to two other sexual assaults where he has not been charged.

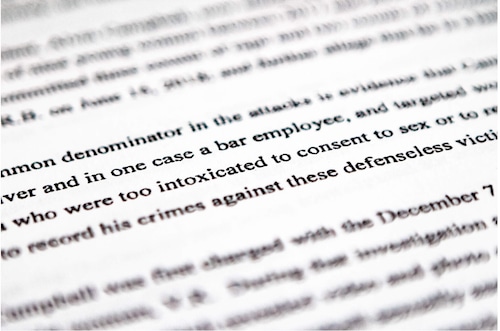

In court, prosecutors and police allege Campbell preyed on intoxicated women at downtown Boston bars for at least three years, often posing as a ride-hailing driver.

The first case mentioned in court records occurred when Campbell was driving for Uber and allegedly took a rider to his home and raped her in July 2016.

Boston police declined to say why they didn’t arrest Campbell at the time, despite DNA evidence linking him to the crime. A spokesman for the Suffolk County district attorney’s office said they couldn’t pursue charges, because the victim declined to testify.

Uber removed Campbell from its platform two days after the alleged assault. But police found his black SUV adorned with Uber stickers more than three years later, and prosecutors say he continued to pick up women in the guise of an Uber driver.

Campbell, who is 6′3″, also allegedly posed as a bouncer in the second case reported to police. Two women who lived together in Boston told police that Campbell started talking to them and claimed to work at the Harp, a popular sports bar near TD Garden where they were hanging out one night in 2017. When the women had trouble ordering a ride, they said Campbell offered to drive them home.

One roommate woke up in her apartment later that night to find Campbell naked on top of her. She told police she pushed him out of her room and locked the door. The other roommate recalled then waking up to Campbell penetrating her, according to the search warrant application. She told police her body felt like “Jell-O.” And just like the first case in 2016, DNA evidence pointed to Campbell.

Prosecutors accused Alvin Campbell in court filings of targeting women who were “too intoxicated to consent to sex.” (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

This time, both victims agreed to testify before a grand jury. But prosecutors withdrew the case before jurors could decide whether to issue an indictment. Privately, the prosecutors said they doubted they could prove that Campbell raped the second roommate while she was sleeping, because the women were drunk and had incomplete memories of what happened.

“Even by her own account, she is not sure whether she actually said no,” prosecutors wrote in an internal memo, which is quoted in a motion filed by Campbell’s lawyers. “It would be nearly impossible to prove lack of consent, due to incapacitation because [she] has some memory of what happened.”

That argument appalled some experts who study sexual assault. “If you’re too incapacitated to give consent, then you cannot give consent,” said Morabito, the UMass Lowell criminologist.

She said prosecutors owe it to victims to bring charges even when cases are complicated.

“Just because these cases are hard to prove is not a reason not to go forward,” Morabito added. “If they are brave enough to come forward and report the crime and go through the sexual assault kit — which we know is incredibly invasive — we owe them that much to take the case further.”

Meanwhile, more victims surfaced. In 2018, a fourth woman told police a man drove her home from Boston’s Howl at the Moon, a bar known for its dueling grand pianos and tropical cocktails.

When she arrived home to Medford, she found she was missing her underwear and thought she had been sexually assaulted. She told police she was heavily intoxicated.

Medford police compared DNA from the investigation against a national law enforcement database. Again, it matched with Campbell. But once again, authorities decided not to make an arrest or file charges. Both Medford police and the Middlesex district attorney’s office declined to explain why.

A woman told Medford police in 2018 she was sexually assaulted by the man who drove her home from Howl at the Moon, a bar on High Street in Boston. DNA evidence later linked Alvin Campbell to the assault. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

A fifth victim came forward in December 2019. The woman told police Campbell picked her up outside the Harp, the same bar where he’d allegedly picked up the two roommates two years earlier. She said she was drunk and mistook Campbell’s SUV for an Uber.

She woke up the next day at Campbell’s apartment in Cumberland, Rhode Island, with vaginal pain and a cut on her breast. Like the other cases, DNA from a rape kit matched Campbell’s information.

Yet once again, police seemed reluctant to take action.

The woman said she tried to report the sexual assault to front desk staff at Boston police headquarters, but they “were not helpful,” according to text messages summarized by Campbell’s lawyers in a discovery motion. The same document states that an officer later told her “she had to make her allegations look like an abduction” for the report to be taken seriously. Boston police did not respond to a request for comment.

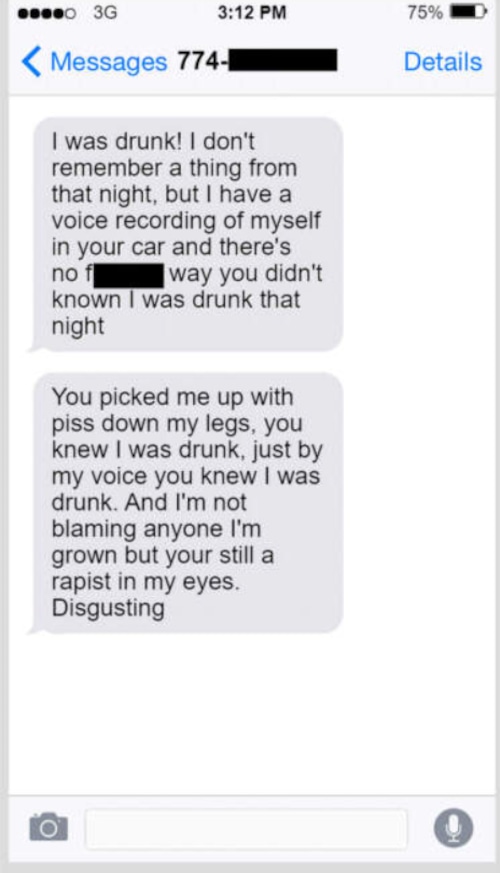

An illustration of texts sent by one of Alvin Campbell’s accusers to his cell phone, as detailed in a search warrant affidavit. Campbell denied he raped her in text responses, the affidavit states. (Redactions by WBUR; illustration created with ifake text message)WBUR

Regardless, Boston police finally arrested Campbell a month after the incident. Investigators searched the phone and found video of Campbell assaulting the victim in his SUV while she was unconscious.

Police also discovered a text message from another woman accusing Campbell of rape after he offered her a ride outside TD Garden.

“I was drunk!” she texted Campbell in 2019. “I could barely speak straight and you decided it was ok to f— me.”

Police soon discovered even more victims. A broader search of Campbell’s phone unearthed photos and videos from at least a half-dozen additional assaults, according to an affidavit attached to the 2020 search warrant. They also found images of two other incidents police were already familiar with but had yet to bring charges – the one at the Harp in 2017 and the one involving the Medford woman in 2018.

Sample HTML block

Both Medford and Boston police declined to answer questions about why they didn’t arrest Campbell or search his phone sooner.

But a spokesman for the Suffolk County district attorney’s office suggested law enforcement didn’t have enough justification to obtain a search warrant for the phone’s contents in the earlier cases. The courts have ruled that police need both reason to think a suspect committed a crime and that the phone contains relevant evidence.

“Police cannot do it simply on a hunch that they might find something,” said Jim Borghesani, the agency’s spokesman.

Boston and Medford police also declined to say why they didn’t take other steps to corroborate victims’ stories when DNA evidence first pointed to Campbell.

For example, a longtime manager of the Harp remembers police requested surveillance footage from the bar when they arrested Campbell in 2020. But he doesn’t recall anyone contacting him after the alleged assaults in 2017, when Campbell allegedly masqueraded as a bouncer inside the tavern to pick up the two roommates.

“They never came down and specifically asked us to do anything or look for people,” Harp manager Jamey Roberts said.

Men walk into the Harp, a popular sports bar near Boston’s TD Garden. This was the tavern where prosecutors say two victims of sexual assault encountered Campbell in 2017. Campbell allegedly posed as a bouncer there and offered them a ride. Another woman accused Campbell of raping her after giving her a ride from the same bar two years later. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

Nor did police arrest Campbell after victims reported two other kinds of physical assaults during the same time period.

In the first incident, a chauffeur said Campbell attacked him outside South Station in 2016 with a sharp object that left cuts on his right ear and head, according to the driver’s request for a harassment prevention order in Lynn District Court. The driver said Campbell fled the scene when police arrived and ignored a verbal order to stop.

And in early 2019, Campbell allegedly slammed two women to the ground outside a Boston nightclub called the Tunnel when one of the women refused to give Campbell her phone number. Again, police decided not to arrest Campbell, but later pursued an assault and battery charge in Boston Municipal Court for attacking one of the women.

A judge dismissed the case in February 2023, saying prosecutors were “not ready for trial.”

A spokesperson for the Suffolk County DA’s office said it couldn’t try the case that day because the victim did not show up in court.

But according to an audio recording of the hearing, Judge Steven Key said prosecutors failed to bring any other witnesses who could identify the people in a video of the incident. In addition, the judge admonished prosecutors for failing to turn over a detective’s interview notes with the victim to the defense lawyers.

Boston police declined to explain why they did not arrest Campbell in either case.

Police and serial rape cases

Stories like Campbell’s are not unique to Boston. Around the country, police have missed opportunities to catch serial rapists again and again. A federal lawsuit last year accused police in Johnson City, Tennessee, of failing to act on complaints that a business owner drugged and raped multiple women.

He has since been accused of assaulting more than 50 unconscious women. And a North Carolina television station, WRAL, found police obtained DNA evidence about a serial rapist in Durham long before he was finally arrested. The man in that case has been charged with four rapes.

In Campbell’s case, some experts wonder whether police may have been hesitant to charge him because of his high-profile sister, Attorney General Andrea Campbell, who was then a Boston city councilor.

“Even if you don’t get that call, you know that you better be careful and not mess this one up because it could come down hard on you,” said Samuel Dordulian, a former sex crimes prosecutor and deputy district attorney for Los Angeles County. “So if it’s one of those cases where it’s 50-50 on whether you should file, you’ll probably hesitate.”

Boston police declined to comment; however, Medford police and prosecutors in Suffolk and Middlesex County all said Campbell’s sister had no impact on the cases.

Medford Police Captain Paul Covino said his department wasn’t even aware that Alvin Campbell was related to Andrea Campbell until informed by a WBUR reporter, even though dozens of news stories mentioned the connection after his arrest.

Molly McGlynn, a spokeswoman for the attorney general’s office, said Andrea Campbell has recused herself from any involvement in the case, has had no contact with law enforcement about the investigation or prosecution and has not talked with her brother since his arrest. In addition, a Boston records officer said the city couldn’t find any email from Campbell’s government account mentioning her brother when she was a city councilor.

In a statement to WBUR, Andrea Campbell said she would “never interfere with or influence any investigation, especially one involving such serious allegations.” She said the prosecution has her “unreserved support.”

Attorney General Andrea Campbell said prosecutors in the case against her brother have her “unreserved support.” In this photo, she speaks at a recent press conference at the State House. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

“I remain horrified, heartbroken, and devastated by this case,” Attorney General Campbell said. “I support survivors of sexual assault without qualification, and I continue to pray for the survivors in this case, who have shown courage in coming forward.”

Alvin Campbell’s trial is currently set for December but has been pushed back repeatedly. That’s in part because he has fired at least four of his court-appointed attorneys, requiring new lawyers to become familiar with the case.

One of Campbell’s attorneys, John Hayes, said that Campbell “fully denies” both the criminal charges and other allegations detailed by police in court records. “Those uncharged cases were dropped for a reason,” he said in late January, shortly before Campbell dismissed him.

Campbell’s various lawyers have also tried to block prosecutors from using photos or video police found on his phone of the alleged assaults. The attorneys argue police didn’t have a legal basis to search his device and misused the information to reach out to women who had never reported any assaults to police.

“The police were no longer investigating reports of sexual assaults, they were seeking out potential victims and telling them that they had been assaulted,” Hayes said.

Alvin Campbell stands in Suffolk Superior Court in 2023. His trial is now slated for December. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)Jesse Costa/WBUR

The public has yet to hear directly from any of the people who were allegedly raped.

In court documents, prosecutors refer to the women only by initials to protect their identities. WBUR was able to identify one of the victims, the woman who accused Campbell in text messages in late 2019 of raping her when she was drunk.

In a brief phone call, the woman said she tries not to think about that night. And she was surprised to hear Campbell had been accused of other assaults when she met him. WBUR does not name sexual assault victims in stories without their consent.

Some experts who study sexual assault say Campbell’s case stands as a warning that the criminal justice system must do more when victims first report sexual assaults to prevent other people from being hurt.

“We need to stop waiting for offenders to have assaulted numerous people before we take action,” said Laura Dunn, an attorney in Washington, D.C. who represents victims of sexual assault. “We need to have prosecutors and law enforcement that are willing to actually enforce the laws on the books.”

WBUR’s Ally Jarmanning and Todd Wallack contributed to this report.